- AI Assitant Summary

- Introduction

- Part One: pre-training phase

- Part Two: downstream tasks

- Personal View

- Reference

- What’s Next?

AI Assitant Summary

This blog discusses the scale of Large Language Models (LLMs) and their impact on performance. LLMs like GPT, LaMDA, and PaLM have billions of parameters, raising questions about the consequences of their continued growth.

The journey of an LLM involves two stages: pre-training and scenario application. Pre-training focuses on optimizing the model using cross-entropy, while scenario application evaluates the model’s performance in specific use cases. Evaluating an LLM’s quality requires considering both stages, rather than relying solely on pre-training indicators.

Increasing training data, model parameters, and training time has been found to enhance performance in the pre-training stage. OpenAI and DeepMind have explored this issue, with OpenAI finding that a combination of more data and parameters, along with fewer training steps, produces the best results. DeepMind considers the amount of training data and model parameters equally important.

The influence of model size on downstream tasks varies. Linear tasks show consistent improvement as the model scales, while breakthrough tasks only benefit from larger models once they reach a critical scale. Tasks involving logical reasoning demonstrate sudden improvement at specific model scales. Some tasks exhibit U-shaped growth, where performance initially declines but then improves with larger models.

Reducing the LLM’s parameters while increasing training data proportionally can decrease the model’s size without sacrificing performance, leading to faster inference speed.

Understanding the impact of model size on both pre-training and downstream tasks is vital for optimizing LLM performance and exploring the potential of these language models.

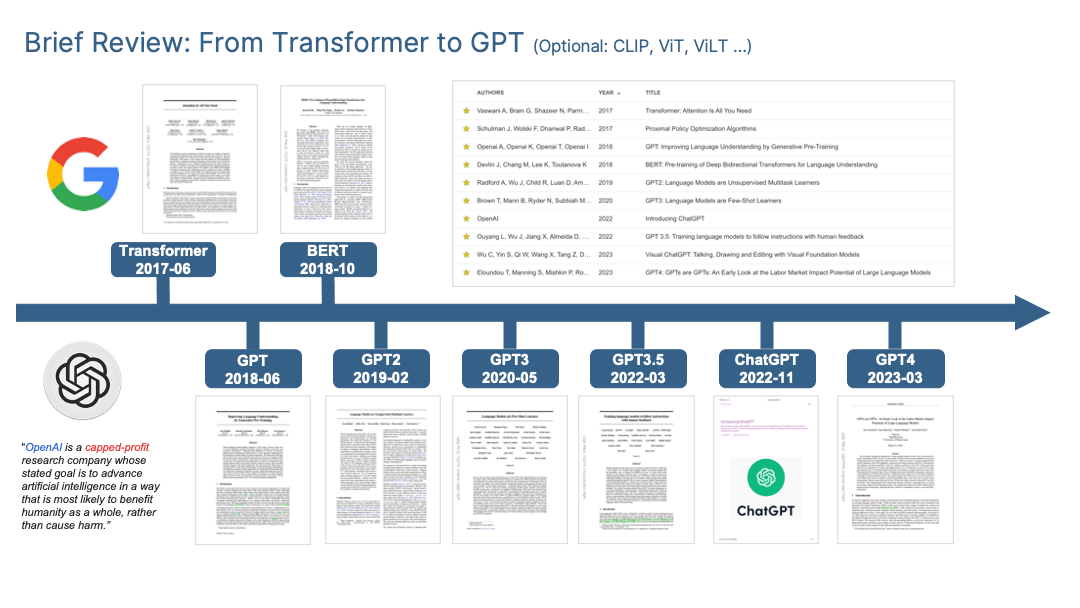

Introduction

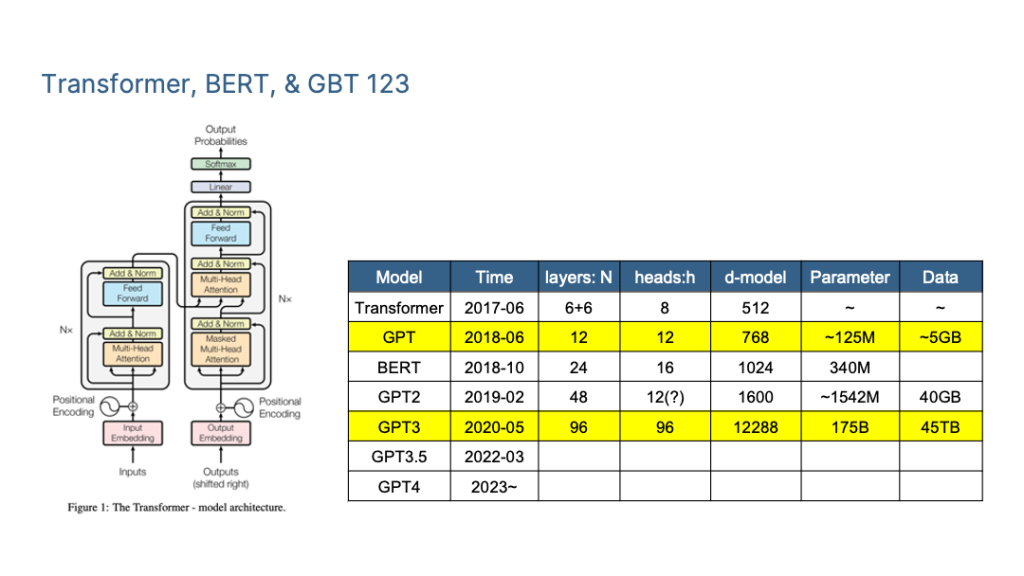

In recent years, we’ve witnessed a surge in the size of Large Language Models (LLMs), with models now boasting over 100 billion parameters becoming the new standard. Think OpenAI’s GPT-3 (175B), Google’s LaMDA (137B), PaLM (540B), and other global heavyweights. China, too, contributes to this landscape with models like Zhiyuan GLM, Huawei’s “Pangu,” Baidu’s “Wenxin,” etc. But here’s the big question: What unfolds as these LLMs continue to grow?

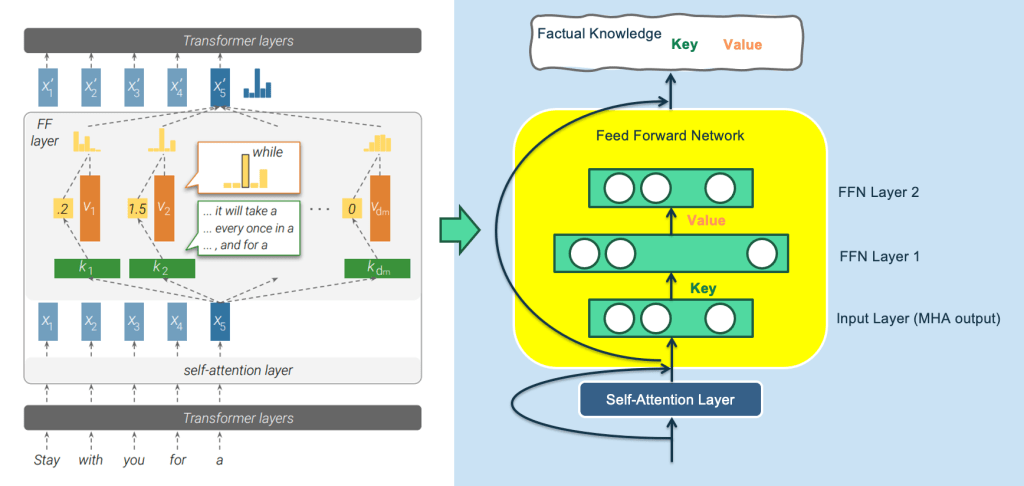

The journey of pre-trained models involves two crucial stages: pre-training and scenario application.

In the pre-training stage, the optimization goal is cross entropy. For autoregressive language models such as GPT, it is to see whether LLM correctly predicts the next word;

However, the real test comes in the scenario application stage, where specific use cases dictate evaluation criteria. Generally, our intuition is that if the LLM has better indicators in the pre-training stage, its ability to solve downstream tasks will naturally be stronger. However, this is not entirely true.

Existing research has proven that the optimization index in the pre-training stage does show a positive correlation with downstream tasks, but it is not completely positive. In other words, it is not enough to only look at the indicators in the pre-training stage to judge whether an LLM model is good enough. Based on this, we will look separately at these two different stages to see what the impact will be as the LLM model increases.

Part One: pre-training phase

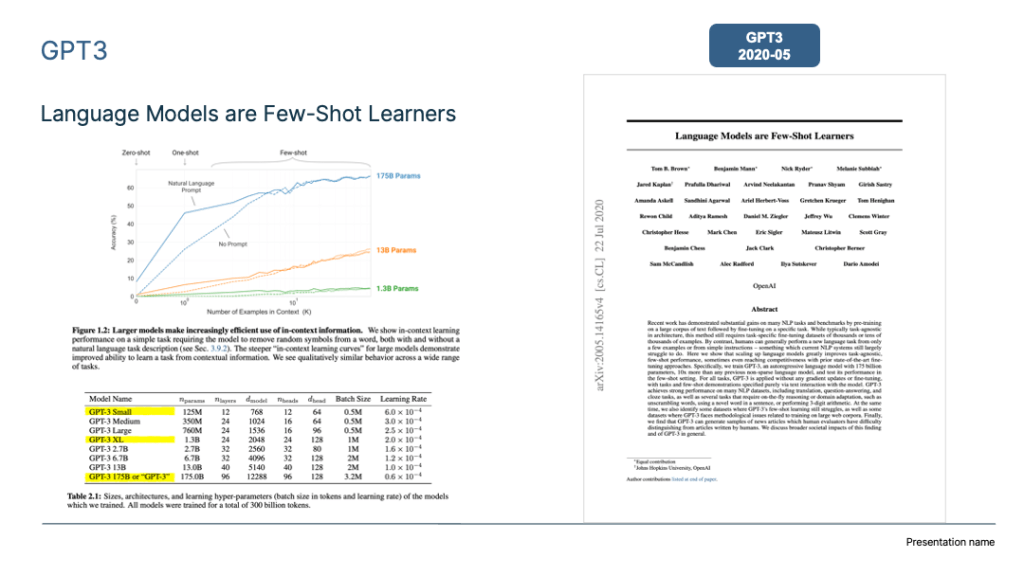

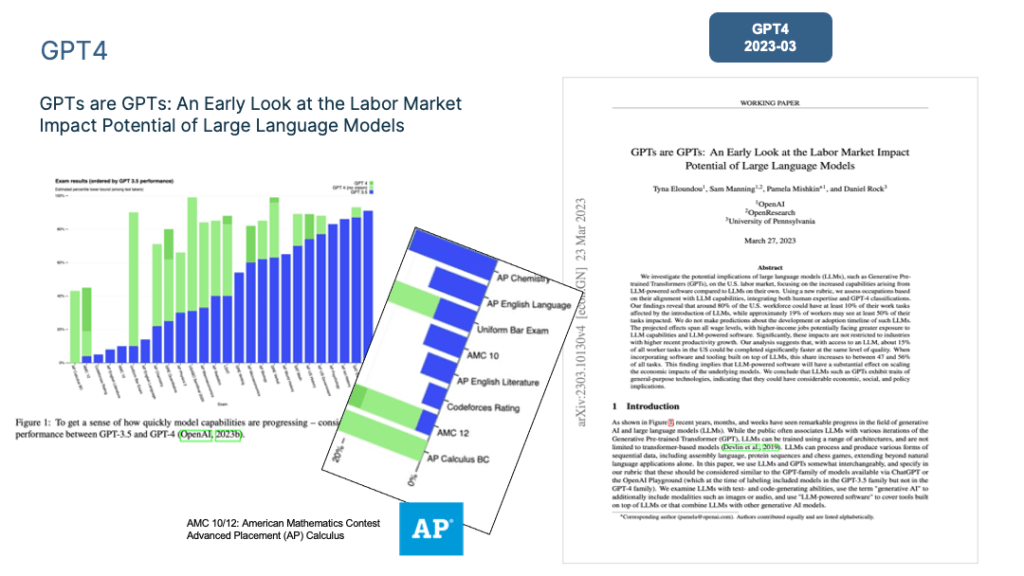

First, let’s look at what happens as the model size gradually increases during the pre-training stage. OpenAI specifically studied this issue in “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models” and proposed the “scaling law” followed by the LLM model.

As shown in the figure above, this study proves that when we independently increase (1) the amount of training data, (2) model parameter size and (3) extend the model training time (such as from 1 Epoch to 2 Epochs), the Loss of the pre-trained model on the test set will decrease monotonically. In other words, the model’s effectiveness is improving steadily.

Since all three factors are important when we actually do pre-training, we have a decision-making problem on how to allocate computing power:

Question: Assuming that the total computing power budget used to train LLM (such as fixed GPU hours or GPU days) is given. How to allocate computing power?

Should we increase the amount of data and reduce model parameters?

Or should we increase the amount of data and model size at the same time but reduce the number of training steps?

Open AI

As one zero-sum game, the scale of one-factor increases, and the scale of other factors must be reduced to keep the total computing power unchanged, so there are various possible computing power allocation plans.

In the end, OpenAI chose to increase the amount of training data and model parameters at the same time but used an early stopping strategy to reduce the number of training steps. Because it proves that: for the two elements of training data volume and model parameters, if you only increase one of them separately, this is not the best choice. It is better to increase both at the same time according to a certain proportion. Its conclusion is to give priority to increasing the model parameters, and then the amount of training data.

Assuming that the total computing power budget used to train LLM increases by 10 times, then the amount of model parameters should be increased by 5.5 times and the amount of training data should be increased by 1.8 times. At this time, the model gets the best performance.

Deep Mind

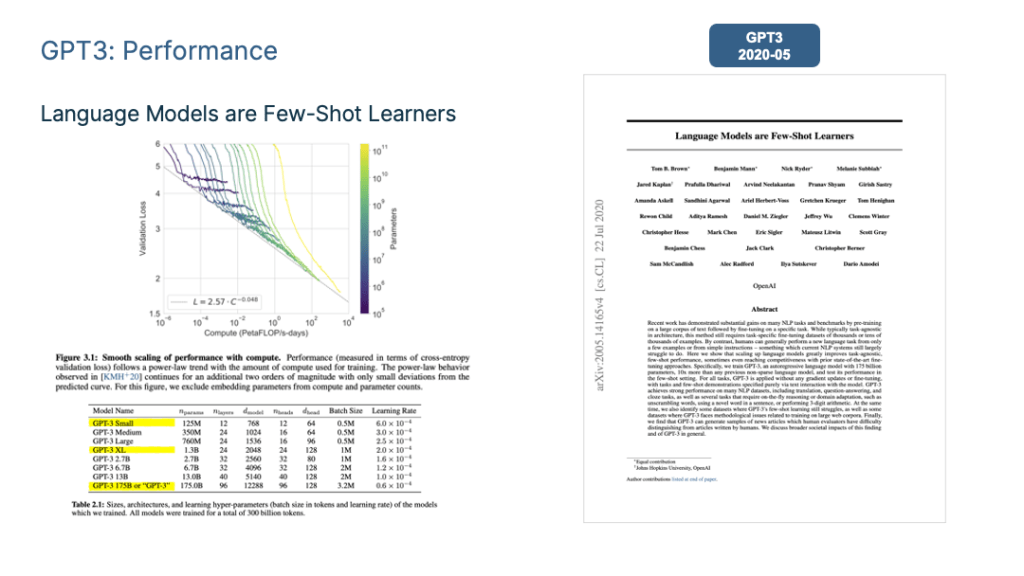

A study by DeepMind (Reference: Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models) explored this issue in more depth.

Its basic conclusions are similar to those of OpenAI. For example, it is indeed necessary to increase the amount of training data and model parameters at the same time, so that the model effect will be better.

Many large models do not consider this when doing pre-training. Many large LLM models were trained just monotonically increasing the model parameters while fixing the amount of training data. This approach is wrong and limits the potential of the LLM model.

However, DeepMind corrects the proportional relationship between the two by OpenAI and believes that the amount of training data and model parameters are equally important.

In other words, assuming that the total computing power budget used to train LLM increases by 10 times, the number of model parameters should be increased by 3.3 times, and the amount of training data should also be increased by 3.3 times to get the best model.

This means that increasing the amount of training data is more important than we previously thought. Based on this understanding, DeepMind chose another configuration in terms of computing power allocation when designing the Chinchilla model: compared with the Gopher model with a data volume of 300B and a model parameter volume of 280B, Chinchilla chose to increase the training data by 4 times, but reduced the model The parameters are reduced to one-fourth that of Gopher, which is about 70B. However, regardless of pre-training indicators or many downstream task indicators, Chinchilla is better than the larger Gopher.

This brings us to the following enlightenment:

We can choose to enlarge the training data and reduce the LLM model parameters in the same proportion to achieve the purpose of greatly reducing the size of the model without reducing the model performance.

Reducing the size of the model has many benefits, such as the inference speed will be much faster when applied. This is undoubtedly a promising development route for LLM.

Part Two: downstream tasks

The above is the impact of the model scale from the pre-training stage. From the perspective of the effect of LLM on solving specific downstream tasks, as the model scale increases, different types of tasks have different performances.

Specifically, there are the following three types of tasks.

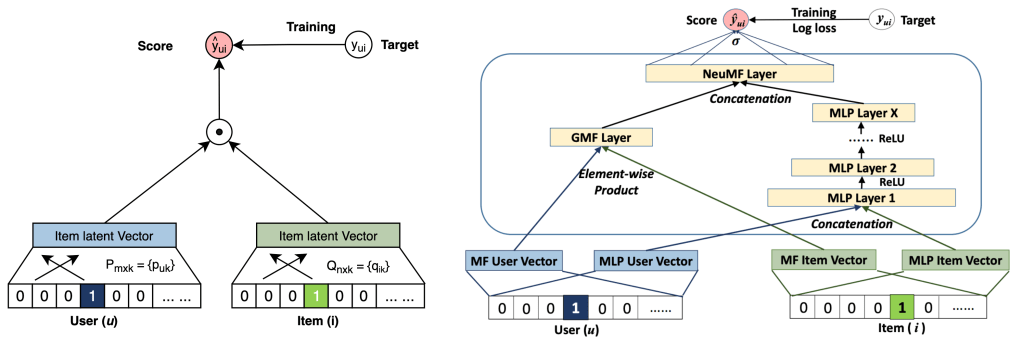

- (a) Tasks that achieve the highest linearity scores see model performance improve predictably with scale and typically rely on knowledge and simple textual manipulations.

- (b) Tasks with high breakthroughs do not see model performance improve until the model reaches a critical scale. These tasks generally require sequential steps or logical reasoning. Around 5% of BIG-bench tasks see models achieve sudden score breakthroughs with increasing scale.

- (c) Tasks that achieve the lowest (negative) linearity scores see model performance degrade with scale.

Linearity Tasks

The first type of task perfectly reflects the scaling law of the LLM model, which means that as the model scale gradually increases, the performance of the tasks gets better and better, as shown in (a) above.

Such tasks usually have the following common characteristics: they are often knowledge-intensive tasks. That is to say, if the LLM model contains more knowledge, the performance of such tasks will be better.

Many studies have proven that the larger the LLM model, the higher the learning efficiency. For the same amount of training data, the larger the model, the better the performance. This shows that even when faced with the same batch of training data, a larger LLM model is relatively more efficient in getting more knowledge than small ones.

What’s more, under normal circumstances, when increasing the LLM model parameters, the amount of training data will often increase simultaneously, which means that large models can learn more knowledge points from more data. These studies can explain the above figure, why as the model size increases, these knowledge-intensive tasks become better and better.

Most traditional NLP tasks are actually knowledge-intensive tasks, and many tasks have achieved great improvement in the past few years, even surpassing human performance. Obviously, this is most likely caused by the increase in the scale of the LLM model, rather than due to a specific technical improvement.

Breakthroughs Tasks

The second type of task demonstrates that LLM has some kind of “Emergent Ability”, as shown in (b) above. The so-called “emergent ability” means that when the model parameter scale fails to reach a certain threshold, the model basically does not have any ability to solve such tasks, which reflects that its performance is equivalent to randomly selecting answers. However, when the model scale spans Once the threshold is exceeded, the LLM model’s effect on such tasks will experience a sudden performance increase.

In other words, model size is the key to unlocking (unlocking) new capabilities of LLM. As the model size becomes larger and larger, more and more new capabilities of LLM will be gradually unlocked.

This is a very magical phenomenon because it means the following possibilities that make people optimistic about the future. Many tasks that cannot be solved well by LLM at present can be solved in future if we continue to make the model larger. Because LLM has “emergent capabilities” to suddenly unlock those limits one day. The growth of the LLM model will bring us unexpected and wonderful gifts.

The article “Beyond the Imitation Game: Quantifying and Extrapolating the Capabilities of Language Models” points out that tasks that embody “emergent capabilities” also have some common features: these tasks generally consist of multiple steps, and to solve these tasks, it is often necessary to first Multiple intermediate steps are solved, and logical reasoning skills play an important role in the final solution of such tasks.

Chain of Thought (CoT) Prompting is a typical technology that enhances the reasoning ability of LLM, which can greatly improve the effect of such tasks. I will discuss the CoT technology in the following blogs.

Here the most important question is, why does LLM have this “emergent ability” phenomenon? The article “Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models” shares several possible explanations:

One possible explanation is that the evaluation indicators of some tasks are not smooth enough. For example, some metrics for generation tasks require that the string output by the model must completely match the standard answer to be considered correct otherwise it will be scored zero.

Thus, even as the model gradually becomes better and outputs more correct character fragments, because it is not completely correct, 0 points will be given for any small errors. Only when the model is large enough, the output Scores are scored when all the output segments are correct. In other words, because the indicator is not smooth enough, it cannot reflect the reality that LLM is actually gradually improving its performance on the task. It seems to be an external manifestation of “emergent ability”.

Another possible explanation is that some tasks are composed of several intermediate steps. As the size of the model increases, the ability to solve each step gradually increases, but as long as one intermediate step is wrong, the final answer will be wrong. This will also lead to this superficial “emergent ability” phenomenon.

Of course, the above explanations are still conjectures at present. As for why LLM has this phenomenon, further and in-depth research is needed.

U-shaped Tasks

There are also a small number of tasks. As the model size increases, the task effect curve shows U-shaped characteristics: as the model size gradually increases, the task effect gradually becomes worse, but when the model size further increases, the effect starts to get better and better. Figure above shows a U-shaped growth trend where the indicator trend of the pink PaLM model on the two tasks.

Why do these tasks appear so special? The article “Inverse Scaling Can Become U-shaped” gives an explanation:

These tasks actually contain two different types of subtasks, one is the real task, and the other is the “interference task ( distractor task)”.

- When the model size is small, it cannot identify any sub-task, so the performance of the model is similar to randomly selecting answers.

- When the model grows to a medium size, it mainly tries to solve the interference task, so it has a negative impact on the real task performance. This is reflected in the decline of the real task effect.

- When the model size is further increased, LLM can ignore the interfering task and perform the real task, which is reflected in the effect starting to grow.

For those tasks whose performance has been declining as the model size increases, if Chain of Thought (CoT) Prompting is used, the performance of some tasks will be converted to follow the Scaling Law. That is, the larger the model size, the better the performance, while other tasks will be converted to a U-shaped growth curve.

This actually shows that this type of task should be a reasoning-type task, so the task performance will change qualitatively after adding CoT.

Personal View

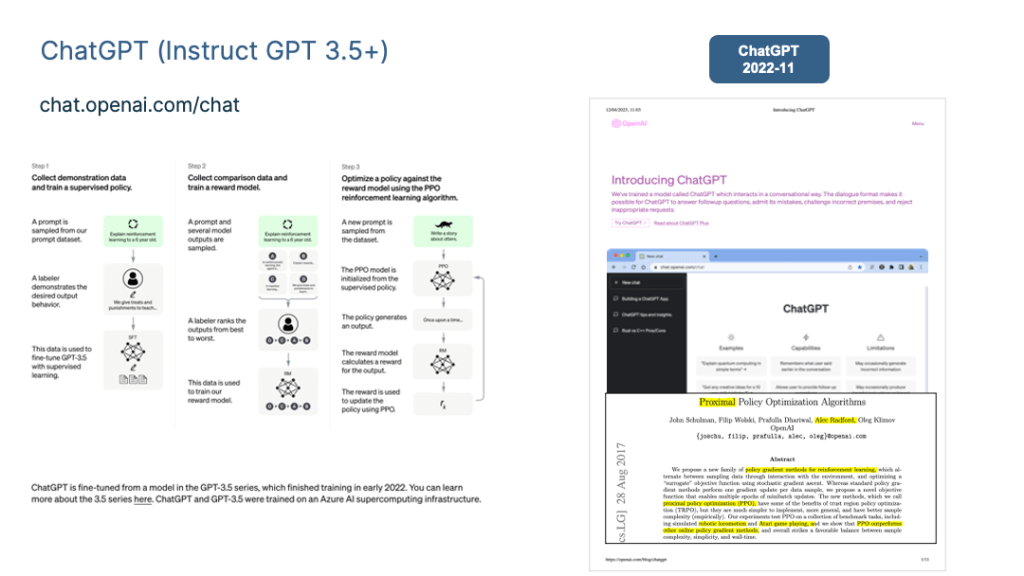

Increasing the size of the LLM model may not seem technically significant, but it is actually very important to build better LLMs. In my opinion, the advancements from Bert to GPT 3 and ChatGPT are likely attributed to the growth of the LLM model size rather than a specific technology. I believe a lot of people want to explore the scale ceiling of the LLM model if possible.

The key to achieving AGI may lie in having large and diverse data, large-scale models, and rigorous training processes. Developing such large LLM models requires high engineering skills from the technical team, which means there is technical content involved.

Increasing the scale of the LLM model has research significance. There are two main reasons why it is valuable.

- Firstly, as the model size grows, the performance of various tasks improves, especially for knowledge-intensive tasks. Additionally, for reasoning and difficult tasks, the effect of adding CoT Prompting follows a scaling law. Therefore, it is important to determine to what extent the scale effect of LLM can solve these tasks.

- Secondly, the “emergent ability” of LLM suggests that increasing the model size may unlock new capabilities that we did not expect. This raises the question of what these capabilities could be.

Considering these factors, it is necessary to continue increasing the model size to explore the limits of its ability to solve different tasks.

Talk is cheap, and in reality, very few AI/ML practitioners have the opportunity or ability to build larger models due to high financial requirements, investment willingness, engineering capabilities, and technical enthusiasm from research institutions. There are probably no more than 10 institutions that can do this on Earth. However, in the future, there may be a possibility of joint efforts between capable institutions to build a Super-Large model:

All (Resources) for One (Model) and One (Model) for All (People).

Modified from Alexandre Dumas, The Three Musketeers

Reference

- OpenAI 2020: Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models (https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.08361)

- DeepMind 2022: Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models (https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.15556)

- BIG-bench Project Team: 2023: Beyond the Imitation Game: Quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models (https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.04615)

- Google 2023: Inverse scaling can become U-shaped (https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.02011)

What’s Next?

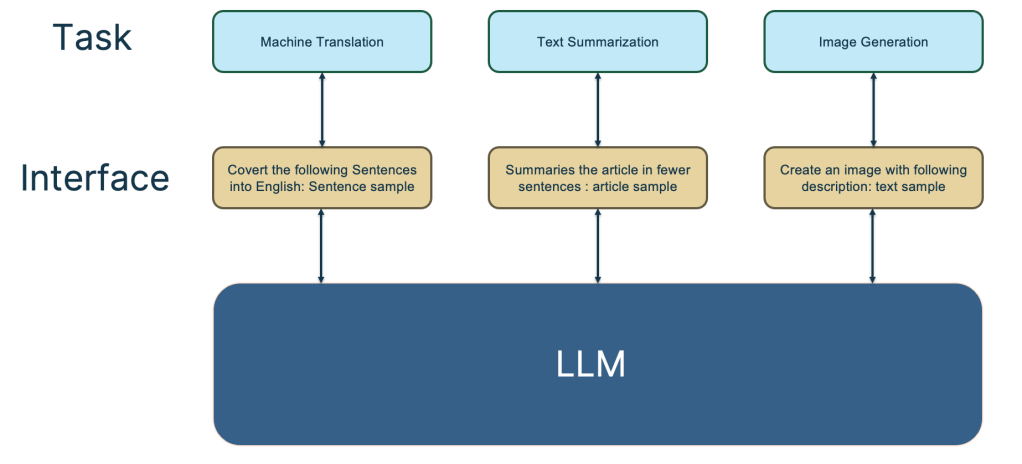

Technical Review 04: Human-Computer Interface: From In Context Learning to Instruct Understanding (ChatGPT)

Previous Blogs

The COVIDSafe app speeds up contacting people exposed to coronavirus (COVID-19). This helps us support and protect you, your friends and family. Please read the content on this page before downloading.

The COVIDSafe app speeds up contacting people exposed to coronavirus (COVID-19). This helps us support and protect you, your friends and family. Please read the content on this page before downloading.