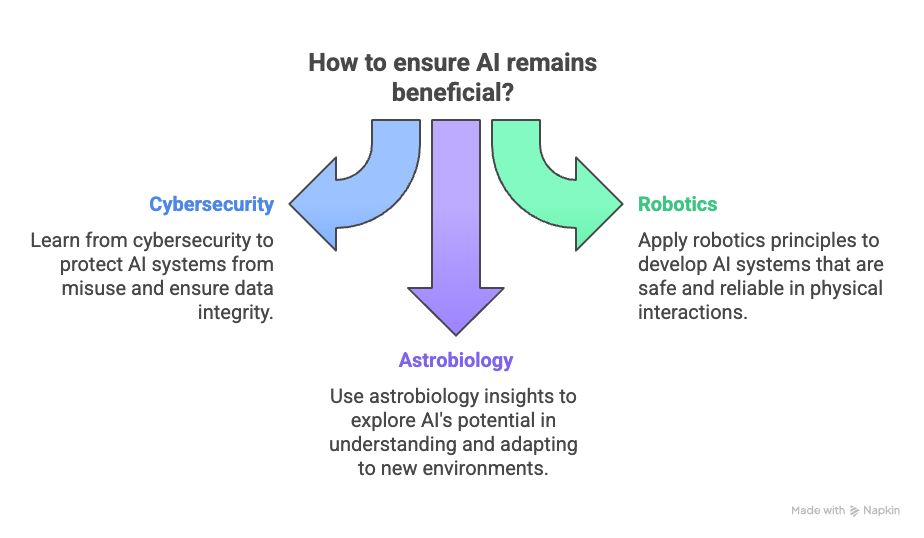

As Artificial Intelligence rapidly evolves, ensuring it remains a beneficial tool rather than a source of unforeseen challenges is paramount; this article explores three critical strategies to keep AI firmly on our side. Our AI researchers can draw lessons from cybersecurity, robotics, and astrobiology side. Source: IEEE Spectrum April 2025; 3 Ways to Keep AI on Our Side: AI Researchers can Draw Lessons from Cybersecurity, Robotics, and Astrobiology

Play the podcast

中文翻译摘要

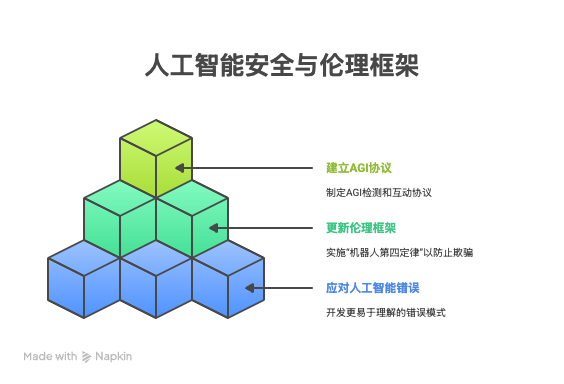

这篇文章提出了确保人工智能安全和有益发展的三个独特且跨学科的策略。

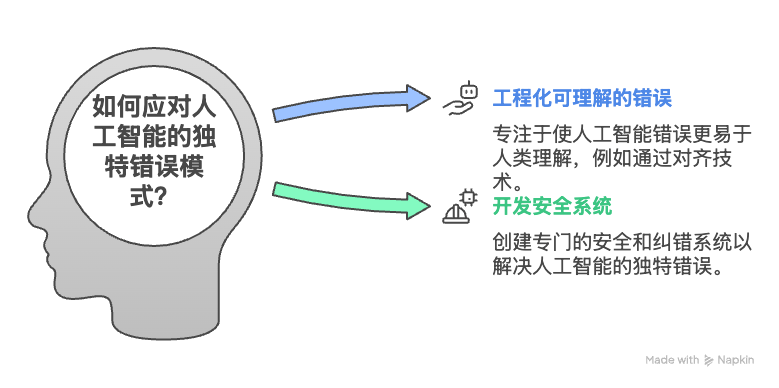

应对人工智能的独特错误模式:布鲁斯·施奈尔(Bruce Schneier)和内森·E·桑德斯(Nathan E. Sanders)(网络安全视角)指出,人工智能系统,特别是大型语言模型(LLMs),其错误模式与人类错误显著不同——它们更难预测,不集中在知识空白处,且缺乏对自身错误的自我意识。他们提出双重研究方向:一是工程化人工智能以产生更易于人类理解的错误(例如,通过RLHF等精炼的对齐技术);二是开发专门针对人工智能独特“怪异”之处的新型安全与纠错系统(例如,迭代且多样化的提示)。

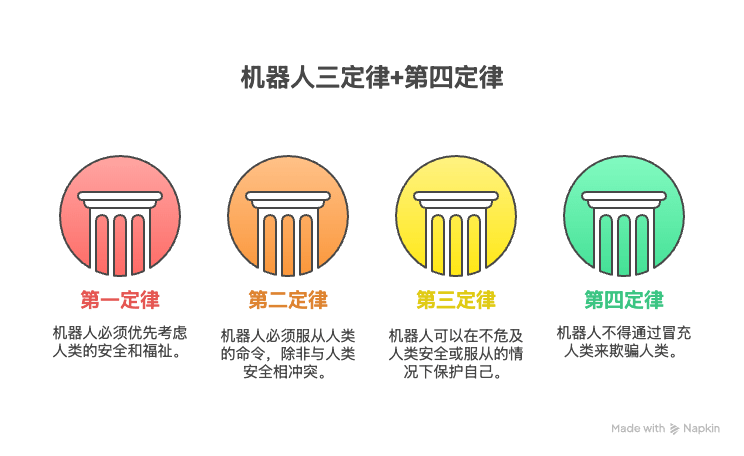

更新伦理框架以打击人工智能欺骗:达里乌什·杰米尔尼亚克(Dariusz Jemielniak)(机器人与互联网文化视角)认为,鉴于人工智能驱动的欺骗行为(包括深度伪造、复杂的错误信息宣传和操纵性人工智能互动)日益增多,艾萨克·阿西莫夫(Isaac Asimov)传统的机器人三定律已不足以应对现代人工智能。他提出一条“机器人第四定律”:机器人或人工智能不得通过冒充人类来欺骗人类。实施这项法律将需要强制性的人工智能披露、清晰标注人工智能生成内容、技术识别标准、法律执行以及公众人工智能素养倡议,以维护人机协作中的信任。

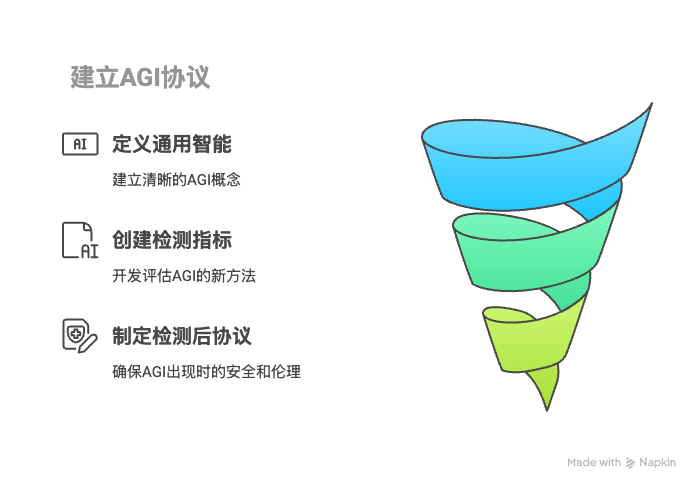

建立通用人工智能(AGI)检测与互动的严格协议:埃德蒙·贝戈利(Edmon Begoli)和阿米尔·萨多夫尼克(Amir Sadovnik)(天体生物学/SETI视角)建议,通用人工智能(AGI)的研究可以借鉴搜寻地外文明(SETI)的方法论。他们主张对AGI采取结构化的科学方法,包括:制定清晰、多学科的“通用智能”及相关概念(如意识)定义;创建超越图灵测试局限性的鲁棒、新颖的AGI检测指标和评估基准;以及制定国际公认的检测后协议,以便在AGI出现时进行验证、确保透明度、安全性和伦理考量。

总而言之,这些观点强调了迫切需要创新、多方面的方法——涵盖安全工程、伦理准则修订以及严格的科学协议制定——以主动管理先进人工智能系统的社会融入和潜在未来轨迹。

- 3 Ways to Keep AI on Our Side

- AI Mistakes Are Very Different from Human Mistakes

- Asimov’s Laws of Robotics Need an Update for AI PROPOSING A FOURTH LAW OF ROBOTICS

- What Can AI Researchers Learn from Alien Hunters?

Abstract: this article presents three distinct, cross-disciplinary strategies for ensuring the safe and beneficial development of Artificial Intelligence.

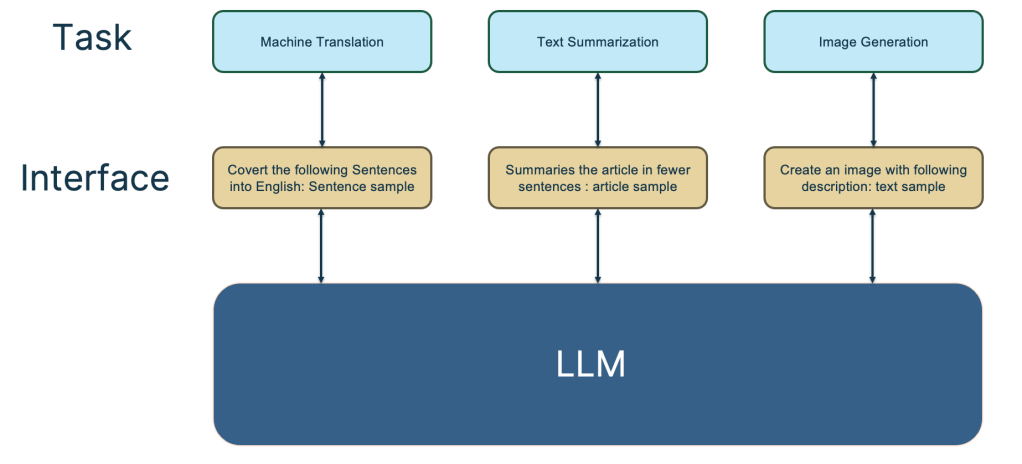

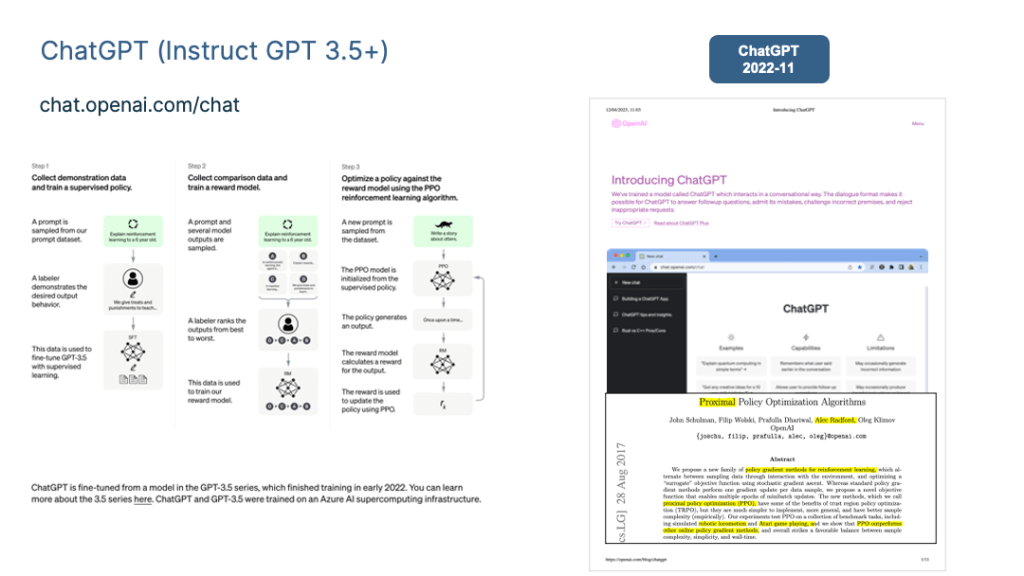

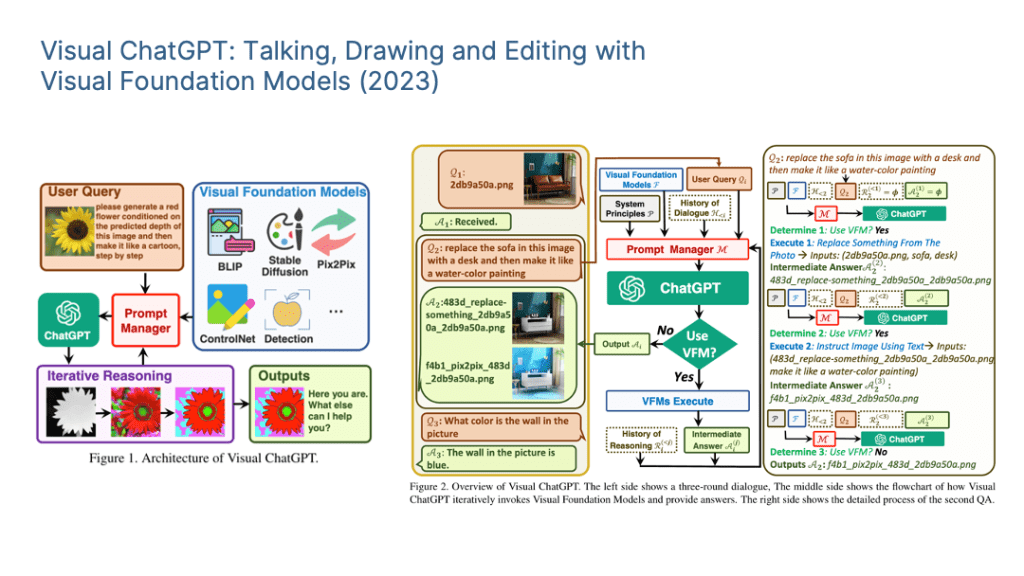

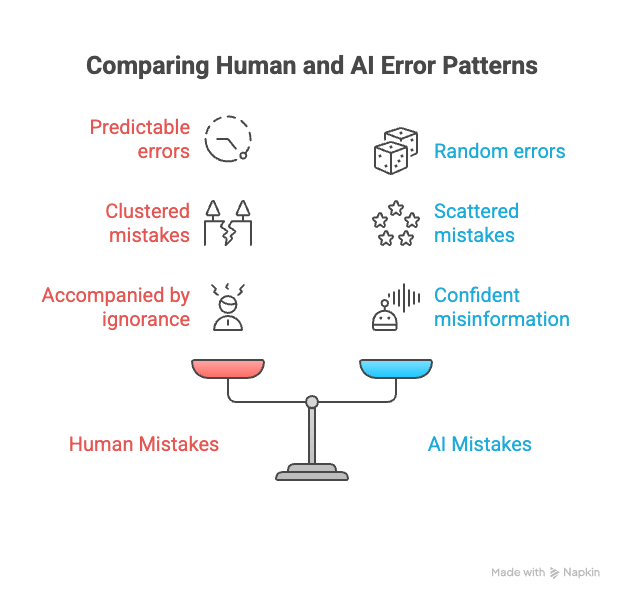

Addressing Idiosyncratic AI Error Patterns (Cybersecurity Perspective): Bruce Schneier and Nathan E. Sanders highlight that AI systems, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), exhibit error patterns significantly different from human mistakes—being less predictable, not clustered around knowledge gaps, and lacking self-awareness of error. They propose a dual research thrust: engineering AIs to produce more human-intelligible errors (e.g., through refined alignment techniques like RLHF) and developing novel security and mistake-correction systems specifically designed for AI’s unique “weirdness” (e.g., iterative, varied prompting).

Updating Ethical Frameworks to Combat AI Deception (Robotics & Internet Culture Perspective): Dariusz Jemielniak argues that Isaac Asimov’s traditional Three Laws of Robotics are insufficient for modern AI due to the rise of AI-enabled deception, including deepfakes, sophisticated misinformation campaigns, and manipulative AI interactions. He proposes a “Fourth Law of Robotics”: A robot or AI must not deceive a human being by impersonating a human being. Implementing this law would necessitate mandatory AI disclosure, clear labeling of AI-generated content, technical identification standards, legal enforcement, and public AI literacy initiatives to maintain trust in human-AI collaboration.

Establishing Rigorous Protocols for AGI Detection and Interaction (Astrobiology/SETI Perspective): Edmon Begoli and Amir Sadovnik suggest that research into Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) can draw methodological lessons from the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). They advocate for a structured scientific approach to AGI that includes:

- Developing clear, multidisciplinary definitions of “general intelligence” and related concepts like consciousness.

- Creating robust, novel metrics and evaluation benchmarks for detecting AGI, moving beyond limitations of tests like the Turing Test.

- Formulating internationally recognized post-detection protocols for validation, transparency, safety, and ethical considerations, should AGI emerge.

Collectively, these perspectives emphasize the urgent need for innovative, multi-faceted approaches—spanning security engineering, ethical guideline revision, and rigorous scientific protocol development—to proactively manage the societal integration and potential future trajectory of advanced AI systems.

Here are the full detailed content:

3 Ways to Keep AI on Our Side

AS ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE reshapes society, our traditional safety nets and ethical frameworks are being put to the test. How can we make sure that AI remains a force for good? Here we bring you three fresh visions for safer AI.

- In the first essay, security expert Bruce Schneier and data scientist Nathan E. Sanders explore how AI’s “weird” error patterns create a need for innovative security measures that go beyond methods honed on human mistakes.

- Dariusz Jemielniak, an authority on Internet culture and technology, argues that the classic robot ethics embodied in Isaac Asimov’s famous rules of robotics need an update to counterbalance AI deception and a world of deepfakes.

- And in the final essay, the AI researchers Edmon Begoli and Amir Sadovnik suggest taking a page from the search for intelligent life in the stars; they propose rigorous standards for detecting the possible emergence of human-level AI intelligence.

As AI advances with breakneck speed, these cross-disciplinary strategies may help us keep our hands on the reins.

AI Mistakes Are Very Different from Human Mistakes

WE NEED NEW SECURITY SYSTEMS DESIGNED TO DEAL WITH THEIR WEIRDNESS

Bruce Schneier & Nathan E. Sanders

HUMANS MAKE MISTAKES all the time. All of us do, every day, in tasks both new and routine. Some of our mistakes are minor, and some are catastrophic. Mistakes can break trust with our friends, lose the confidence of our bosses, and sometimes be the difference between life and death.

Over the millennia, we have created security systems to deal with the sorts of mistakes humans commonly make. These days, casinos rotate their dealers regularly, because they make mistakes if they do the same task for too long. Hospital personnel write on patients’ limbs before surgery so that doctors operate on the correct body part, and they count surgical instruments to make sure none are left inside the body. From copyediting to double-entry bookkeeping to appellate courts, we humans have gotten really good at preventing and correcting human mistakes.

Humanity is now rapidly integrating a wholly different kind of mistakemaker into society: AI. Technologies like large language models (LLMs) can perform many cognitive tasks traditionally fulfilled by humans, but they make plenty of mistakes. You may have heard about chatbots telling people to eat rocks or add glue to pizza. What differentiates AI systems’ mistakes from human mistakes is their weirdness. That is, AI systems do not make mistakes in the same ways that humans do.

Much of the risk associated with our use of AI arises from that difference. We need to invent new security systems that adapt to these differences and prevent harm from AI mistakes.

IT’S FAIRLY EASY to guess when and where humans will make mistakes. Human errors tend to come at the edges of someone’s knowledge: Most of us would make mistakes solving calculus problems. We expect human mistakes to be clustered: A single calculus mistake is likely to be accompanied by others. We expect mistakes to wax and wane depending on factors such as fatigue and distraction. And mistakes are typically accompanied by ignorance: Someone who makes calculus mistakes is also likely to respond “I don’t know” to calculus-related questions.

To the extent that AI systems make these humanlike mistakes, we can bring all of our mistake-correcting systems to bear on their output. But the current crop of AI models—particularly LLMs—make mistakes differently.

AI errors come at seemingly random times, without any clustering around particular topics. The mistakes tend to be more evenly distributed through the knowledge space; an LLM might be equally likely to make a mistake on a calculus question as it is to propose that cabbages eat goats. And AI mistakes aren’t accompanied by ignorance. An LLM will be just as confident when saying something completely and obviously wrong as it will be when saying something true.

The inconsistency of LLMs makes it hard to trust their reasoning in complex, multistep problems. If you want to use an AI model to help with a business problem, it’s not enough to check that it understands what factors make a product profitable; you need to be sure it won’t forget what money is.

THIS SITUATION INDICATES two possible areas of research: engineering LLMs to make mistakes that are more humanlike, and building new mistake-correcting systems that deal with the specific sorts of mistakes that LLMs tend to make.

We already have some tools to lead LLMs to act more like humans. Many of these arise from the field of “alignment” research, which aims to make models act in accordance with the goals of their human developers. One example is the technique that was arguably responsible for the breakthrough success of ChatGPT: reinforcement learning with human feedback. In this method, an AI model is rewarded for producing responses that get a thumbs-up from human evaluators. Similar approaches could be used to induce AI systems to make humanlike mistakes, particularly by penalizing them more for mistakes that are less intelligible.

When it comes to catching AI mistakes, some of the systems that we use to prevent human mistakes will help. To an extent, forcing LLMs to double-check their own work can help prevent errors. But LLMs can also confabulate seemingly plausible yet truly ridiculous explanations for their flights from reason.

Other mistake-mitigation systems for AI are unlike anything we use for humans. Because machines can’t get fatigued or frustrated, it can help to ask an LLM the same question repeatedly in slightly different ways and then synthesize its responses. Humans won’t put up with that kind of annoying repetition, but machines will.

RESEARCHERS ARE still struggling to understand where LLM mistakes diverge from human ones. Some of the weirdness of AI is actually more humanlike than it first appears.

Small changes to a query to an LLM can result in wildly different responses, a problem known as prompt sensitivity. But, as any survey researcher can tell you, humans behave this way, too. The phrasing of a question in an opinion poll can have drastic impacts on the answers.

LLMs also seem to have a bias toward repeating the words that were most common in their training data—for example, guessing familiar place names like “America” even when asked about more exotic locations. Perhaps this is an example of the human “availability heuristic” manifesting in LLMs; like humans, the machines spit out the first thing that comes to mind rather than reasoning through the question. Also like humans, perhaps, some LLMs seem to get distracted in the middle of long documents; they remember more facts from the beginning and end.

In some cases, what’s bizarre about LLMs is that they act more like humans than we think they should. Some researchers have tested the hypothesis that LLMs perform better when offered a cash reward or threatened with death. It also turns out that some of the best ways to “jailbreak” LLMs (getting them to disobey their creators’ explicit instructions) look a lot like the kinds of social-engineering tricks that humans use on each otherfor example, pretending to be someone else or saying that the request is just a joke. But other effective jailbreaking techniques are things no human would ever fall for. One group found that if they used ASCII art (constructions of symbols that look like words or pictures) to pose dangerous questions, like how to build a bomb, the LLM would answer them willingly.

Humans may occasionally make seemingly random, incomprehensible, and inconsistent mistakes, but such occurrences are rare and often indicative of more serious problems. We also tend not to put people exhibiting these behaviors in decision-making positions. Likewise, we should confine AI decision-making systems to applications that suit their actual abilities—while keeping the potential ramifications of their mistakes firmly in mind.

Asimov’s Laws of Robotics Need an Update for AI PROPOSING A FOURTH LAW OF ROBOTICS

Dariusz Jemielniak

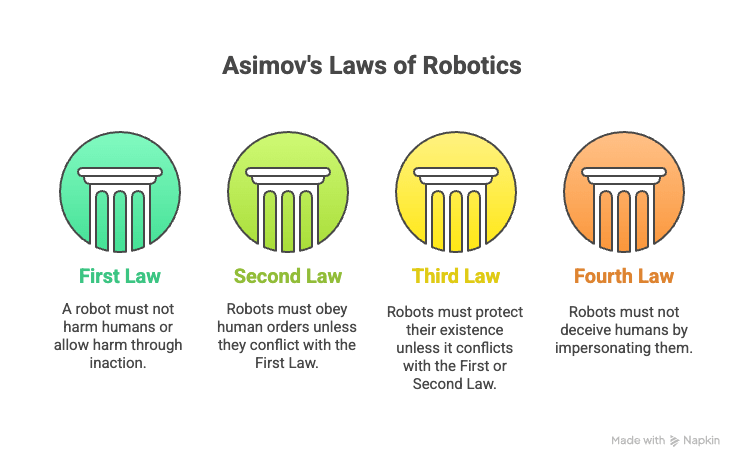

IN 1942, the legendary science fiction author Isaac Asimov introduced his Three Laws of Robotics in his short story “Runaround.” The laws were later popularized in his seminal story collection I, Robot.

- FIRST LAW: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- SECOND LAW: A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- THIRD LAW: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

While drawn from works of fiction, these laws have shaped discussions of robot ethics for decades. And as AI systems—which can be considered virtual robots—have become more sophisticated and pervasive, some technologists have found Asimov’s framework useful for considering the potential safeguards needed for AI that interacts with humans.

But the existing three laws are not enough. Today, we are entering an era of unprecedented human-AI collaboration that Asimov could hardly have envisioned. The rapid advancement of generative AI, particularly in language and image generation, has created challenges beyond Asimov’s original concerns about physical harm and obedience.

THE PROLIFERATION of AI-enabled deception is particularly concerning. According to the FBI’s most recent Internet Crime Report, cybercrime involving digital manipulation and social engineering results in annual losses counted in the billions. The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity’s ENISA Threat Landscape 2023 highlighted deepfakes—synthetic media that appear genuine—as an emerging threat to digital identity and trust.

Social-media misinformation is a huge problem today. I studied it during the pandemic extensively and can say that the proliferation of generative AI tools has made its detection increasingly difficult. AI-generated propaganda is often just as persuasive as or even more persuasive than traditional propaganda, and bad actors can very easily use AI to create convincing content. Deepfakes are on the rise everywhere. Botnets can use AI-generated text, speech, and video to create false perceptions of widespread support for any political issue. Bots are now capable of making phone calls while impersonating people, and AI scam calls imitating familiar voices are increasingly common. Any day now, we can expect a boom in video-call scams based on AI-rendered overlay avatars, allowing scammers to impersonate loved ones and target the most vulnerable populations.

Even more alarmingly, children and teenagers are forming emotional attachments to AI agents, and are sometimes unable to distinguish between interactions with real friends and bots online. Already, there have been suicides attributed to interactions with AI chatbots.

In his 2019 book Human Compatible (Viking), the eminent computer scientist Stuart Russell argues that AI systems’ ability to deceive humans represents a fundamental challenge to social trust. This concern is reflected in recent policy initiatives, most notably the European Union’s AI Act, which includes provisions requiring transparency in AI interactions and transparent disclosure of AI-generated content. In Asimov’s time, people couldn’t have imagined the countless ways in which artificial agents could use online communication tools and avatars to deceive humans.

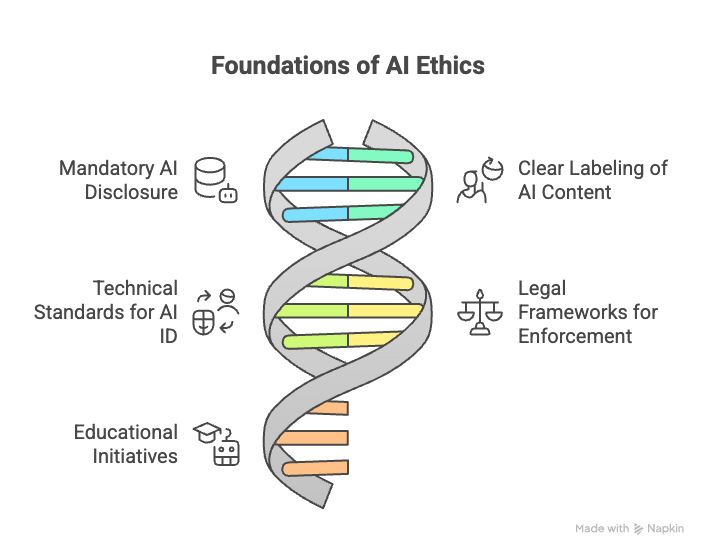

Therefore, we must make an addition to Asimov’s laws.

FOURTH LAW: A robot or AI must not deceive a human being by impersonating a human being.

WE NEED CLEAR BOUNDARIES. While human-AI collaboration can be constructive, AI deception undermines trust and leads to wasted time, emotional distress, and misuse of resources. Artificial agents must identify themselves to ensure our interactions with them are transparent and productive. AI-generated content should be clearly marked unless it has been significantly edited and adapted by a human.

Implementation of this Fourth Law would require

- mandatory AI disclosure in direct interactions,

- clear labeling of AI-generated content,

- technical standards for AI identification,

- legal frameworks for enforcement, and

- educational initiatives to improve AI literacy.

Of course, all this is easier said than done. Enormous research efforts are already underway to find reliable ways to watermark or detect AI-generated text, audio, images, and videos. But creating the transparency I’m calling for is far from a solved problem.

The future of human-AI collaboration depends on maintaining clear distinctions between human and artificial agents. As noted in the IEEE report Ethically Aligned Design, transparency in AI systems is fundamental to building public trust and ensuring the responsible development of artificial intelligence.

Asimov’s complex stories showed that even robots that tried to follow the rules often discovered there were unintended consequences to their actions. Still, having AI systems that are at least trying to follow Asimov’s ethical guidelines would be a very good start.

What Can AI Researchers Learn from Alien Hunters?

THE SETI INSTITUTE’S APPROACH HAS LESSONS FOR RESEARCH ON ARTIFICIAL GENERAL INTELLIGENCE

Edmon Begoli & Amir Sadovnik

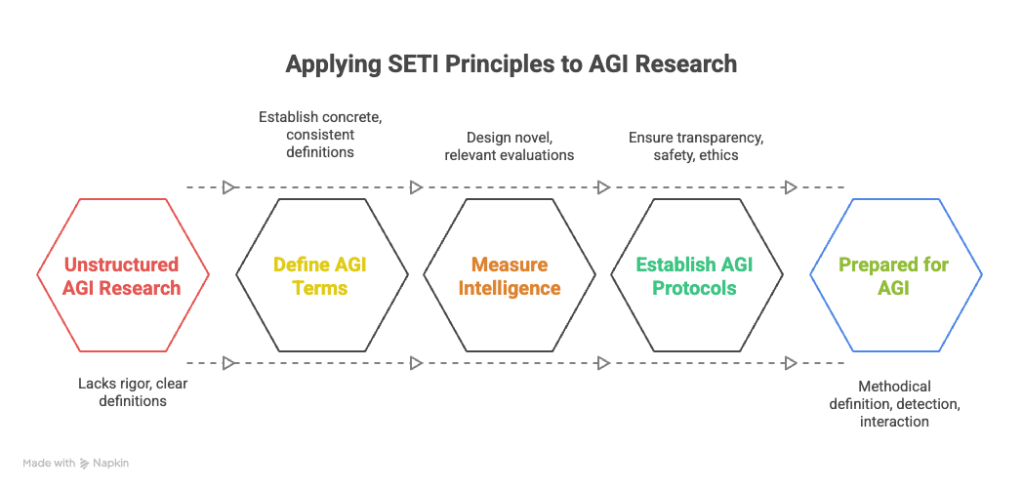

THE EMERGENCE OF artificial general intelligence (systems that can perform any intellectual task a human can) could be the most important event in human history. Yet AGI remains an elusive and controversial concept. We lack a clear definition of what it is, we don’t know how to detect it, and we don’t know how to interact with it if it finally emerges.

What we do know is that today’s approaches to studying AGI are not nearly rigorous enough. Companies like OpenAI are actively striving to create AGI, but they include research on AGI’s social dimensions and safety issues only as their corporate leaders see fit. And academic institutions don’t have the resources for significant efforts.

We need a structured scientific approach to prepare for AGI. A useful model comes from an unexpected field: the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI. We believe that the SETI Institute’s work provides a rigorous framework for detecting and interpreting signs of intelligent life.

The idea behind SETI goes back to the beginning of the space age. In their 1959 Nature paper, the physicists Giuseppe Cocconi and Philip Morrison suggested ways to search for interstellar communication. Given the uncertainty of extraterrestrial civilizations’ existence and sophistication, they theorized about how we should best “listen” for messages from alien societies.

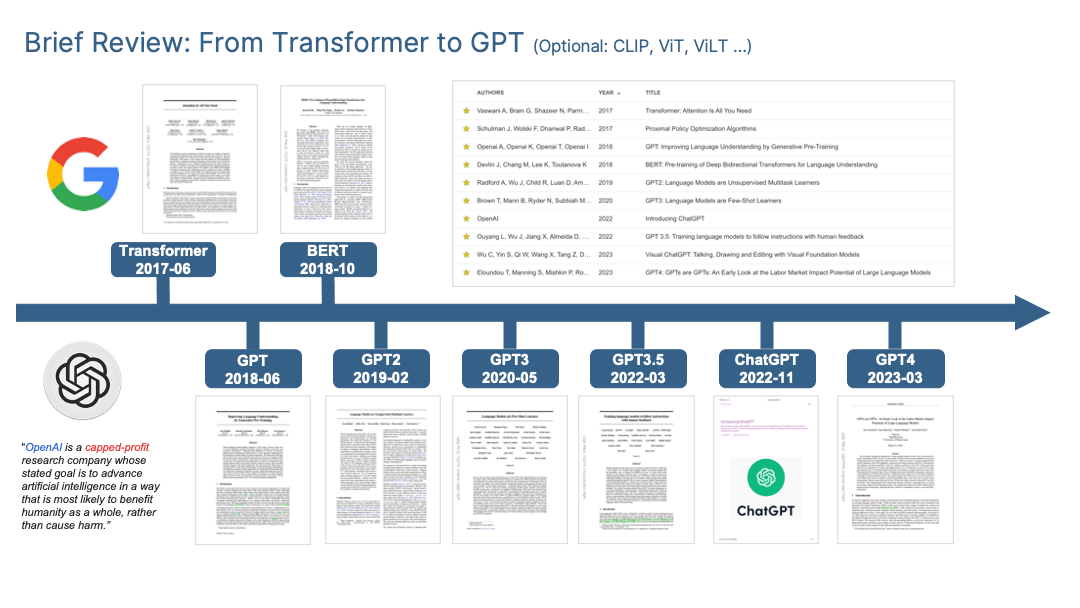

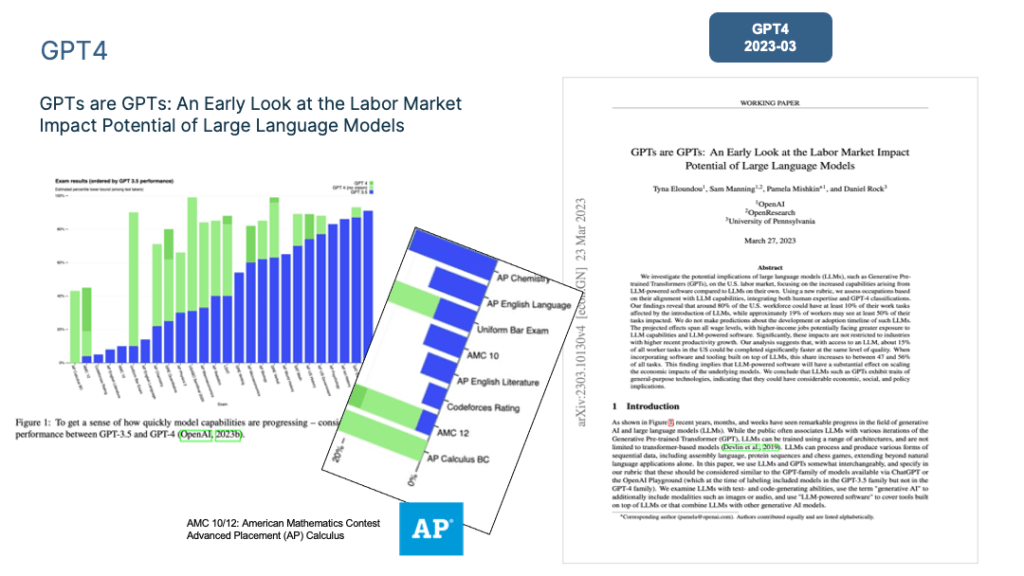

We argue for a similar approach to studying AGI, in all its uncertainties. The last few years have shown a vast leap in AI capabilities. The large language models (LLMs) that power chatbots like ChatGPT and enable them to converse convincingly with humans have renewed the discussion of AGI. One notable 2023 preprint even argued that ChatGPT shows “sparks” of AGI, and today’s most cutting-edge language models are capable of sophisticated reasoning and outperform humans in many evaluations.

While these claims are intriguing, there are reasons to be skeptical. In fact, a large group of scientists have argued that the current set of tools won’t bring us any closer to true AGI. But given the risks associated with AGI, if there is even a small likelihood of it occurring, we must make a serious effort to develop a standard definition of AGI, establish a SETI-like approach to detecting it, and devise ways to safely interact with it if it emerges.

THE CRUCIAL FIRST step is to define what exactly to look for. In SETI’s case, researchers decided to look for certain narrowband signals that would be distinct from other radio signals present in the cosmic background. These signals are considered intentional and only produced by intelligent life. None have been found so far.

In the case of AGI, matters are far more complicated. Today, there is no clear definition of artificial general intelligence. The term is hard to define because it contains other imprecise and controversial terms. Although intelligence has been defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills,” there is still much debate on which skills are involved and how they can be measured. The term general is also ambiguous. Does an AGI need to be able to do absolutely everything a human can do?

One of the first missions of a “SETI for AGI” project must be to clearly define the terms general and intelligence so the research community can speak about them concretely and consistently. These definitions need to be grounded in disciplines such as computer science, measurement science, neuroscience, psychology, mathematics, engineering, and philosophy.

There’s also the crucial question of whether a true AGI must include consciousness and self-awareness. These terms also have multiple definitions, and the relationships between them and intelligence must be clarified. Although it’s generally thought that consciousness isn’t necessary for intelligence, it’s often intertwined with discussions of AGI because creating a self-aware machine would have many philosophical, societal, and legal implications.

NEXT COMES the task of measurement. In the case of SETI, if a candidate narrowband signal is detected, an expert group will verify that it is indeed from an extraterrestrial source. They’ll use established criteria—for example, looking at the signal type and checking for repetition—and conduct assessments at multiple facilities for additional validation.

How to best measure computer intelligence has been a long-standing question in the field. In a famous 1950 paper, Alan Turing proposed the “imitation game,” more widely known as the Turing Test, which assesses whether human interlocutors can distinguish if they are chatting with a human or a machine. Although the Turing Test was useful in the past, the rise of LLMs has made clear that it isn’t a complete enough test to measure intelligence. As Turing himself noted, the relationship between imitating language and thinking is still an open question.

Future appraisals must be directed at different dimensions of intelligence. Although measures of human intelligence are controversial, IQ tests can provide an initial baseline to assess one dimension. In addition, cognitive tests on topics such as creative problem-solving, rapid learning and adaptation, reasoning, and goal-directed behavior would be required to assess general intelligence.

But it’s important to remember that these cognitive tests were designed for humans and might contain assumptions that might not apply to computers, even those with AGI abilities. For example, depending on how it’s trained, a machine may score very high on an IQ test but remain unable to solve much simpler tasks. In addition, an AI may have new abilities that aren’t measurable by our traditional tests. There’s a clear need to design novel evaluations that can alert us when meaningful progress is made toward AGI.

IF WE DEVELOP AGI, we must be prepared to answer questions such as: Is the new form of intelligence a new form of life? What kinds of rights does it have? What are the potential safety concerns, and what is our approach to containing the AGI entity?

Here, too, SETI provides inspiration. SETI’s postdetection protocols emphasize validation, transparency, and international cooperation, with the goal of maximizing the credibility of the process, minimizing sensationalism, and bringing structure to such a profound event. Likewise, we need internationally recognized AGI protocols to bring transparency to the entire process, apply safety-related best practices, and begin the discussion of ethical, social, and philosophical concerns.

We readily acknowledge that the SETI analogy can go only so far. If AGI emerges, it will be a human-made phenomenon. We will likely gradually engineer AGI and see it slowly emerge, so detection might be a process that takes place over a period of years, if not decades. In contrast, the existence of extraterrestrial life is something that we have no control over, and contact could happen very suddenly.

The consequences of a true AGI are entirely unpredictable. To best prepare, we need a methodical approach to defining, detecting, and interacting with AGI, which could be the most important development in human history.