TL;DR: This blog explores the profound influence of ChatGPT, awakening various sectors – the general public, academia, and industry – to the developmental philosophy of Large Language Models (LLMs). It delves into OpenAI’s prominent role and analyzes the transformative effect of LLMs on Natural Language Processing (NLP) research paradigms. Additionally, it contemplates future prospects for the ideal LLM.

- AI Assitant Summary

- Introduction

- NLP Research Paradigm Transformation

- The Ideal Large Language Model (LLM)

- Reference

AI Assitant Summary

This blog discusses the impact of ChatGPT and the awakening it brought to the understanding of Large Language Models (LLM). It emphasizes the importance of the development philosophy behind LLM and notes OpenAI’s leading position, followed by Google, with DeepMind and Meta catching up. The article highlights OpenAI’s contributions to LLM technology and the global hierarchy in this domain.

The blog is divided into two main sections: the NLP research paradigm transformation and the ideal Large Language Model (LLM).

In the NLP research paradigm transformation section, there are two significant paradigm shifts discussed. The first shift, from deep learning to two-stage pre-trained models, marked the introduction of models like Bert and GPT. This shift led to the decline of intermediate tasks in NLP and the standardization of technical approaches across different NLP subfields.

The second paradigm shift focuses on the move from pre-trained models to General Artificial Intelligence (AGI). The blog highlights the impact of ChatGPT in bridging the gap between humans and LLMs, allowing LLMs to adapt to human commands and preferences. It also suggests that many independently existing NLP research fields will be incorporated into the LLM technology system, while other fields outside of NLP will also be included. The ultimate goal is to achieve an ideal LLM that is a domain-independent general artificial intelligence model.

In the section on the ideal Large Language Model (LLM), the blog discusses the characteristics and capabilities of an ideal LLM. It emphasizes the self-learning capabilities of LLMs, the ability to tackle problems across different subfields, and the importance of adapting LLMs to user-friendly interfaces. It also mentions the impact of ChatGPT in integrating human preferences into LLMs and the future potential for LLMs to expand into other fields such as image processing and multimodal tasks.

Overall, the blog provides insights into the impact of ChatGPT, the hierarchy in LLM development, and the future directions for LLM technology.

Introduction

Since the emergence of OpenAI ChatGPT, many people and companies have been both surprised and awakened in academia and industry. I was pleasantly surprised because I did not expect a Large Language Model (LLM) to be as effective at this level, and I was also shocked because most of our academic & industrial understanding of LLM and its development philosophy is far from the world’s most advanced ideas. This blog series covers my reviews, reflections, and thoughts about LLM.

From GPT 3.0, LLM is not merely a specific technology; it actually embodies a developmental concept that outlines where LLM should be heading. From a technical standpoint, I personally believe that the main gap exists in the different understanding of LLM and its development philosophy for the future regardless of the financial resources to build LLM.

While many AI-related companies are currently in a “critical stage of survival,” I don’t believe it is as dire as it may seem. OpenAI is the only organization with a forward-thinking vision in the world. ChatGPT has demonstrated exceptional performance that has left everyone trailing behind, even super companies like Google lag behind in their understanding of the LLM development concept and version of their products.

In the field of LLM (Language Model), there is a clear hierarchy. OpenAI is leading internationally, being about six months to a year ahead of Google and DeepMind, and approximately two years ahead of China. Google holds the second position, with technologies like PaLM 1/2, Pathways and Generative AI on GCP Vertex AI, which aligns with their technical vision. These were launched between February and April of 2022, around the same time as OpenAI’s InstructGPT 3.5. This highlights the difference between Google and OpenAI.

DeepMind has mainly focused on reinforcement learning for games and AI in science. They started paying attention to LLM in 2021, and they are currently catching up. Meta AI, previously known as Facebook AI, hasn’t prioritized LLM in the past, but they are now trying to catch up with recently open-sourced Llama 2. These institutions are currently among the best in the field.

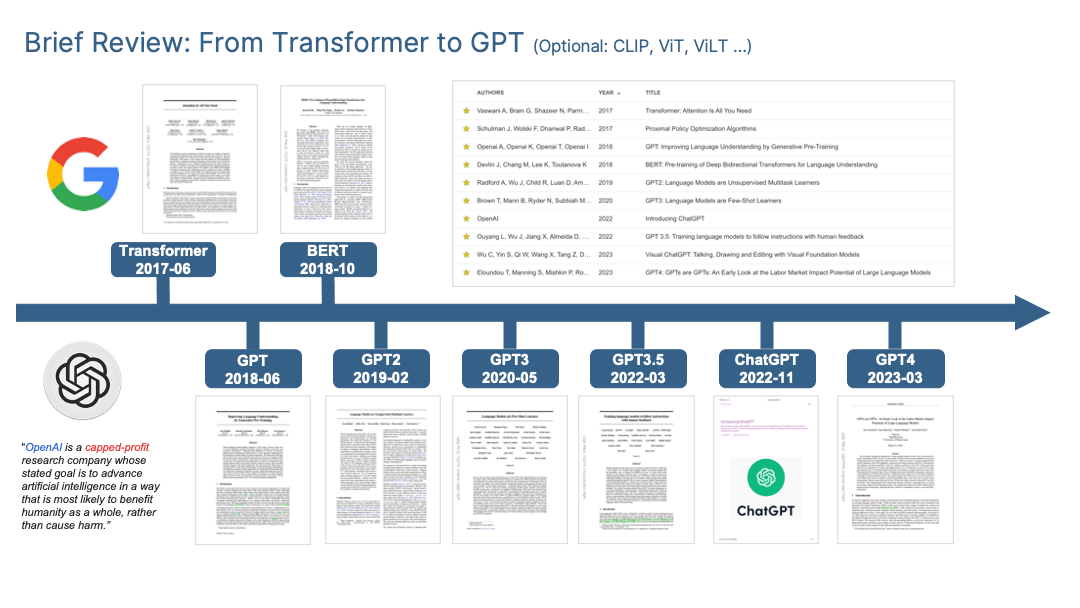

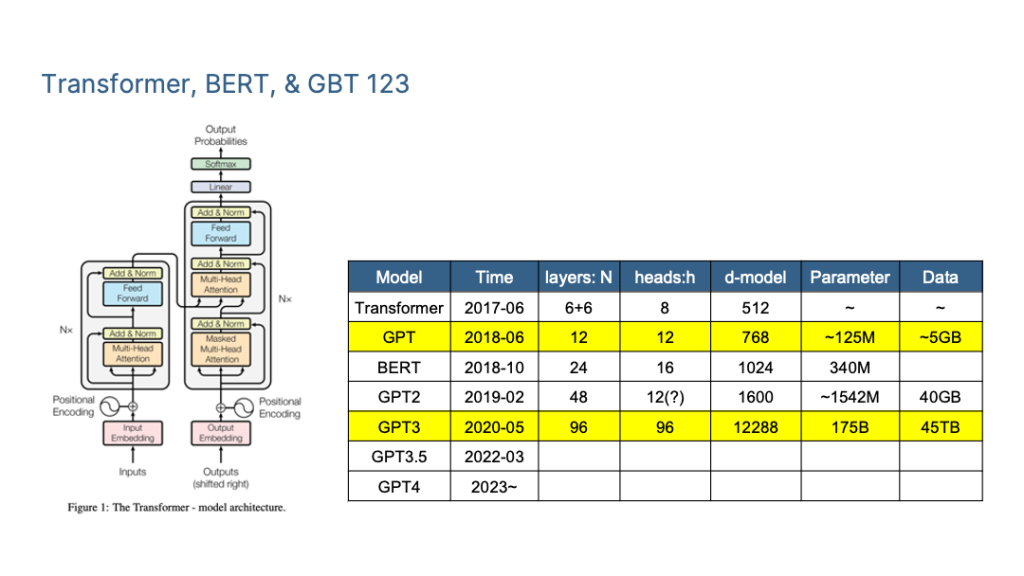

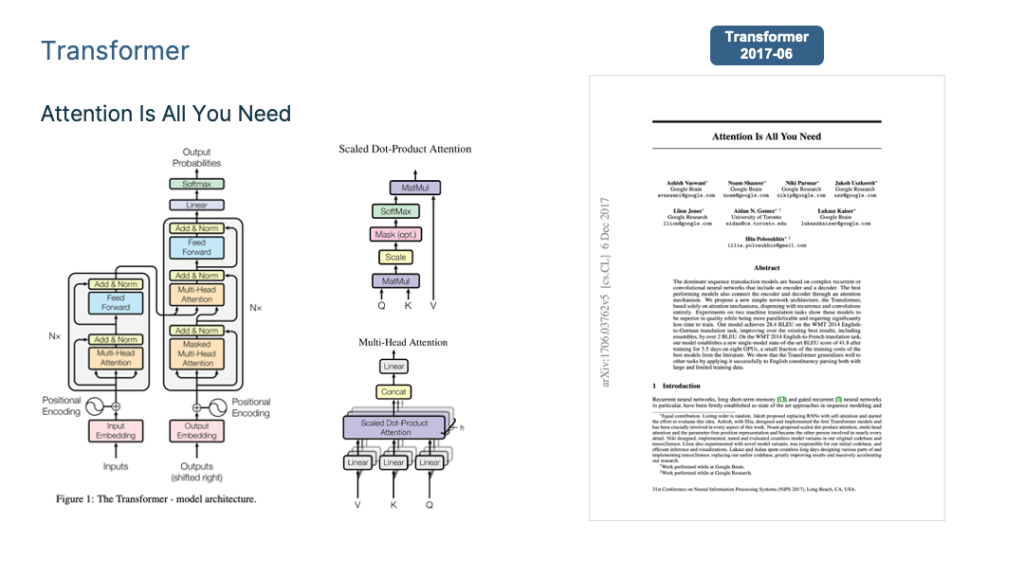

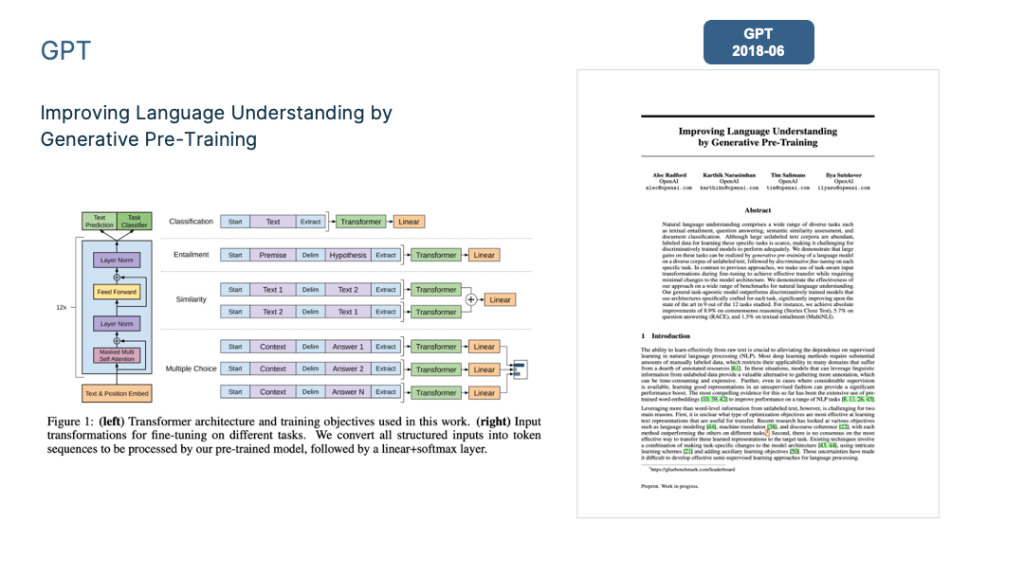

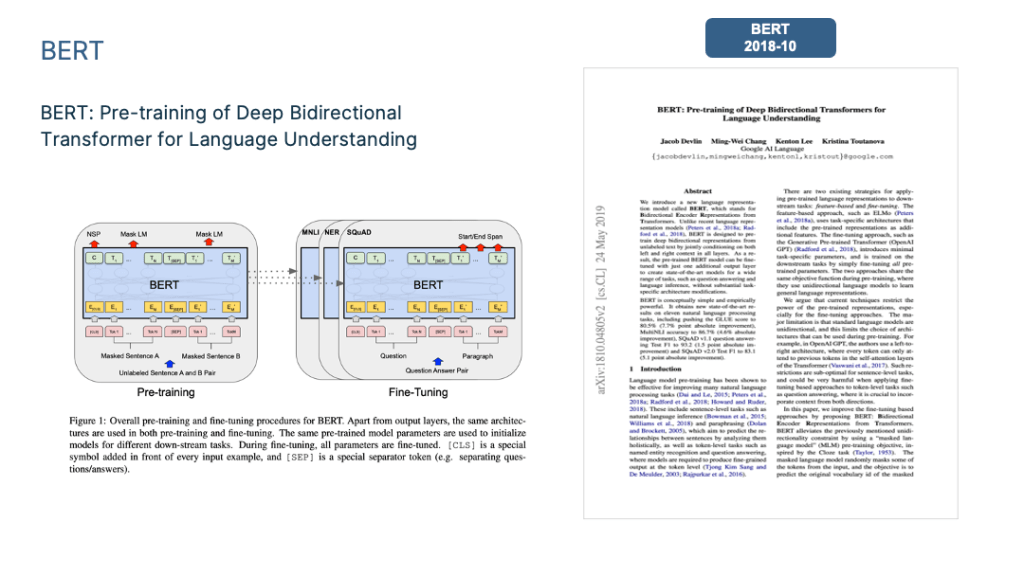

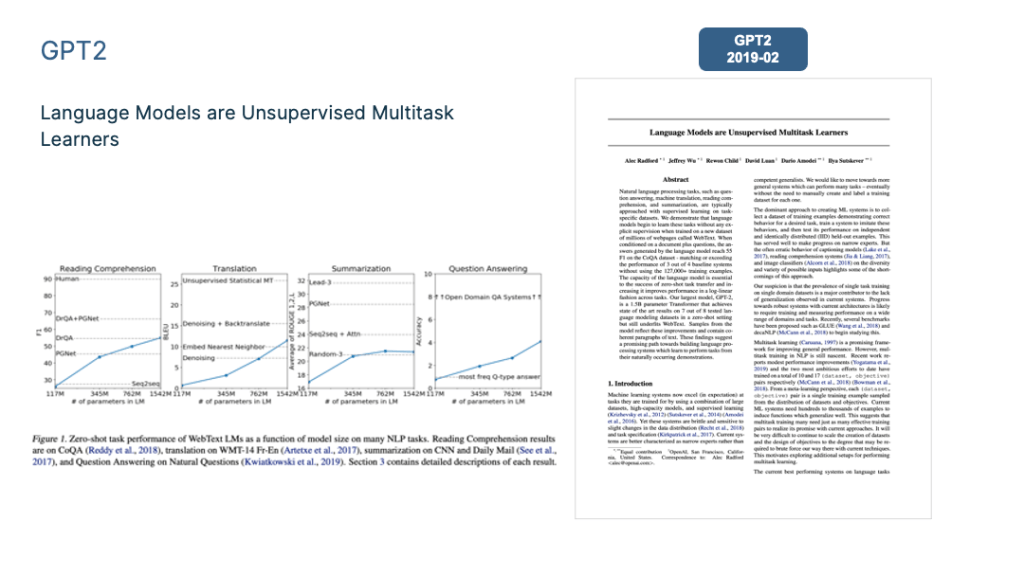

To summarize the mainstream LLM technology I mainly focus on the Transformer, BERT, GPT and ChatGPT <=4.0.

NLP Research Paradigm Transformation

Taking a look back at the early days of deep learning in Natural Language Processing (NLP), we can see significant milestones over the past two decades. There have been two major shifts in the technology of NLP.

Paradigm Shift 1.0 (2013): From Deep Learning to Two-Stage Pre-trained Models

The period of this paradigm shift encompasses roughly the time frame from the introduction of deep learning into the field of NLP, around 2013, up until just before the emergence of GPT 3.0, which occurred around May 2020.

Prior to the rise of models like BERT and GPT, the prevailing technology in the NLP field was deep learning. It was primarily reliant on two core technologies:

- A plethora of enhanced LSTM models and a smaller number of improved ConvNet models served as typical Feature Extractors.

- A prevalent technical framework for various specific tasks was based on Sequence-to-Sequence (or Encoder-Decoder) Architectures coupled with Attention mechanisms.

With these foundational technologies in place, the primary research focus in deep learning for NLP revolved around how to effectively increase model depth and parameter capacity. This involved the continual addition of deeper LSTM or CNN layers to encoders and decoders with the aim of enhancing layer depth and model capacity. Despite these efforts successfully deepening the models, their overall effectiveness in solving specific tasks was somewhat limited. In other words, the advantages gained compared to non-deep learning methods were not particularly significant.

The difficulties that have held back the success of deep learning in NLP can be attributed to two main issues:

- Scarcity of Training Data: One significant challenge is the lack of enough training data for specific tasks. As the model becomes more complex, it requires more data to work effectively. This used to be a major problem in NLP research before the introduction of pre-trained models.

- Limited Ability of LSTM/CNN Feature Extractors: Another issue is that the feature extractors using LSTM/CNN are not versatile enough. This means that, no matter how much data you have, the model struggles to make good use of it because it can’t effectively capture and utilize the information within the data.

These two factors seem to be the primary obstacles that have prevented deep learning from making significant advancements in the field of NLP.

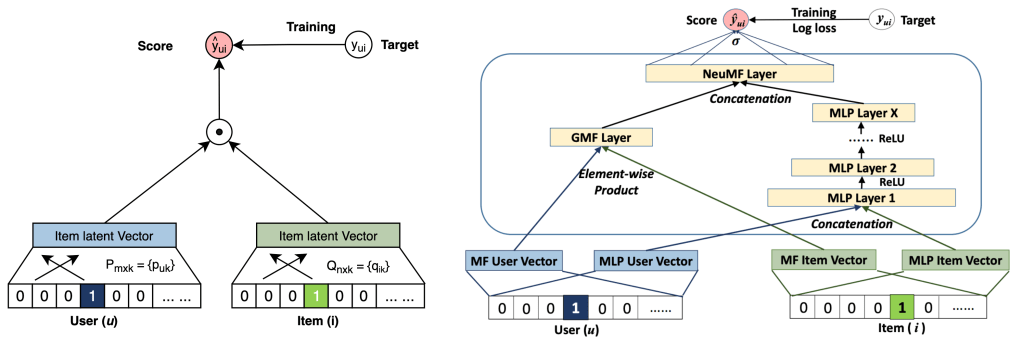

The advent of two pre-training models, Bert and GPT, marks a significant technological advancement in the field of NLP.

About a year after the introduction of Bert, the technological landscape had essentially consolidated into these two core models.

This development has had a profound impact on both academic research and industrial applications, leading to a complete transformation of the research paradigm in the field. The impact of this paradigm shift can be observed in two key areas:

- firstly, a decline and, in some cases, the gradual obsolescence of certain NLP research subfields;

- secondly, the growing standardization of technical methods and frameworks across different NLP subfields.

Impact 1: The Decline of Intermediate Tasks

In the field of NLP, tasks can be categorized into two major groups: “intermediate tasks” and “final tasks.”

- Intermediate tasks, such as word segmentation, part-of-speech tagging, and syntactic analysis, don’t directly address real-world needs but rather serve as preparatory stages for solving actual tasks. For example, the user doesn’t require a syntactic analysis tree; they just want an accurate translation.

- In contrast, “final tasks,” like text classification and machine translation, directly fulfil user needs.

Intermediate tasks initially arose due to the limited capabilities of early NLP technology. Researchers segmented complex problems like Machine Translation into simpler intermediate stages because tackling them all at once was challenging. However, the emergence of Bert/GPT has made many of these intermediate tasks obsolete. These models, through extensive pre-training on data, have incorporated these intermediate tasks as linguistic features within their parameters. As a result, we can now address final tasks directly, without modelling these intermediary processes.

Even Chinese word segmentation, a potentially controversial example, follows the same principle. We no longer need to determine which words should constitute a phrase; instead, we let Large Language Models (LLM) learn this as a feature. As long as it contributes to task-solving, LLM will naturally grasp it. This may not align with conventional human word segmentation rules.

In light of these developments, it’s evident that with the advent of Bert/GPT, NLP intermediate tasks are gradually becoming obsolete.

Impact 2: Standardization of Technical Approaches Across All Areas

Within the realm of “final tasks,” there are essentially two categories: natural language understanding tasks and natural language generation tasks.

- Natural language understanding tasks, such as text classification and sentiment analysis, involve categorizing input text.

- In contrast, natural language generation tasks encompass areas like chatbots, machine translation, and text summarization, where the model generates output text based on input.

Since the introduction of the Bert/GPT models, a clear trend towards technical standardization has emerged.

Firstly, feature extractors across various NLP subfields have shifted from LSTM/CNN to Transformer. The writing was on the wall shortly after Bert’s debut, and this transition became an inevitable trend.

Currently, Transformer not only unifies NLP but is also gradually supplanting other models like CNN in various image processing tasks. Multi-modal models have similarly adopted the Transformer framework. This Transformer journey, starting in NLP, is expanding into various AI domains, kickstarted by the Vision Transformer (ViT) in late 2020. This expansion shows no signs of slowing down and is likely to accelerate further.

Secondly, most NLP subfields have adopted a two-stage model: model pre-training followed by application fine-tuning or Zero/Few Shot Prompt application.

To be more specific, various NLP tasks have converged into two pre-training model frameworks:

- For natural language understanding tasks, the “bidirectional language model pre-training + application fine-tuning” model represented by Bert has become the standard.

- For natural language generation tasks, the “autoregressive language model (i.e., one-way language model from left to right) + Zero/Few Shot Prompt” model represented by GPT 2.0 is now the norm.

Though these models may appear similar, they are rooted in distinct development philosophies, leading to divergent future directions. Regrettably, many of us initially underestimated the potential of GPT’s development route, instead placing more focus on Bert’s model.

Paradigm Shift 2.0 (2020): Moving from Pre-Trained Models to General Artificial Intelligence (AGI)

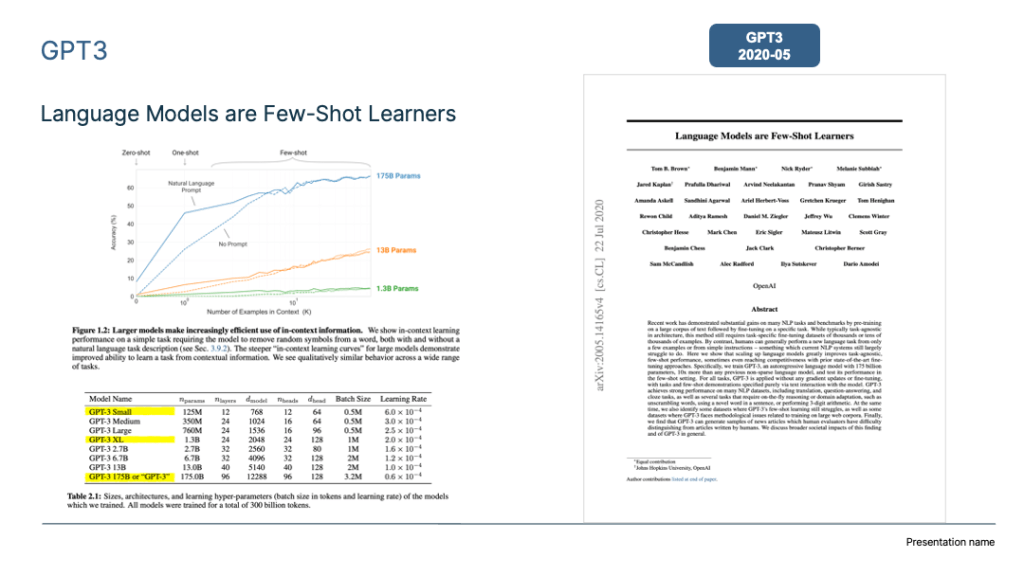

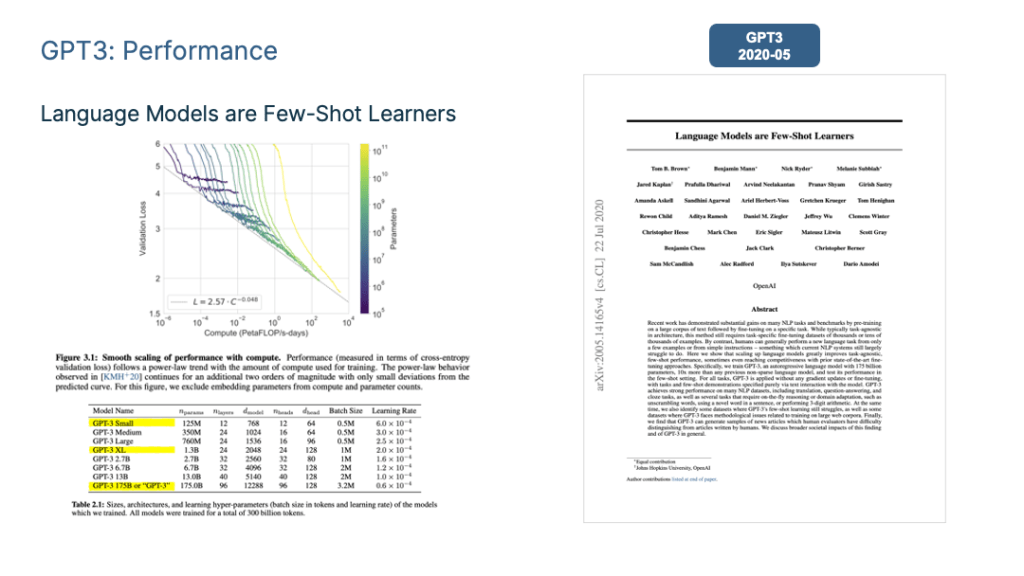

This paradigm shift began around the time GPT 3.0 emerged, approximately in June 2020, and we are currently undergoing this transition.

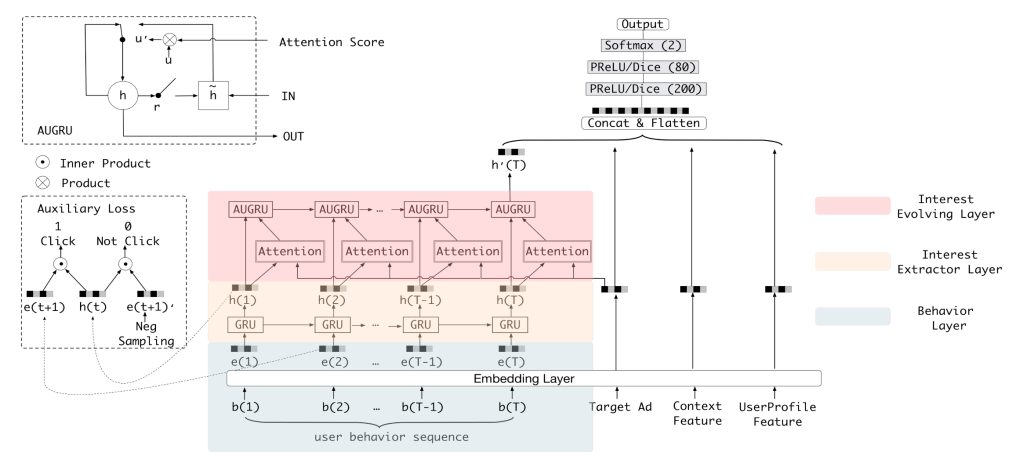

ChatGPT served as a pivotal point in initiating this paradigm shift. However, before the appearance of InstructGPT, Large Language Models (LLM) were in a transitional phase.

Transition Period: Dominance of the “Autoregressive Language Model + Prompting” Model as Seen in GPT 3.0

As mentioned earlier, during the early stages of pre-training model development, the technical landscape primarily converged into two distinct paradigms: the Bert mode and the GPT mode. Bert was the favoured path, with several technical improvements aligning with that direction. However, as technology progressed, we observed that the largest LLM models currently in use are predominantly based on the “autoregressive language model + Prompting” model, similar to GPT 3.0. Models like GPT 3, PaLM, GLaM, Gopher, Chinchilla, MT-NLG, LaMDA, and more all adhere to this model, without exceptions.

Why has this become the prevailing trend? There are likely two key reasons driving this shift, and I believe they are at the forefront of this transition.

Firstly, Google’s T5 model plays a crucial role in formally uniting the external expressions of both natural language understanding and natural language generation tasks. In the T5 model, tasks that involve natural language understanding, like text classification and determining sentence similarity (marked in red and yellow in the figure above), align with generation tasks in terms of input and output format.

This means that classification tasks can be transformed within the LLM model to generate corresponding category strings, achieving a seamless integration of understanding and generation tasks. This compatibility allows natural language generation tasks to harmonize with natural language understanding tasks, a feat that would be more challenging to accomplish the other way around.

The second reason is that if you aim to excel at zero-shot prompting or few-shot prompting, the GPT mode is essential.

Now, recent studies, as referenced in “On the Role of Bidirectionality in Language Model Pre-Training,” demonstrate that when downstream tasks are resolved during fine-tuning, the Bert mode outperforms the GPT mode. Conversely, if you employ zero-shot or few-shot prompting to tackle downstream tasks, the GPT mode surpasses the Bert mode.

But this leads to an important question: Why do we strive to use zero-shot or few-shot prompting for task completion? To answer this question, we first need to address another: What type of Large Language Model (LLM) is the most ideal for our needs?

The Ideal Large Language Model (LLM)

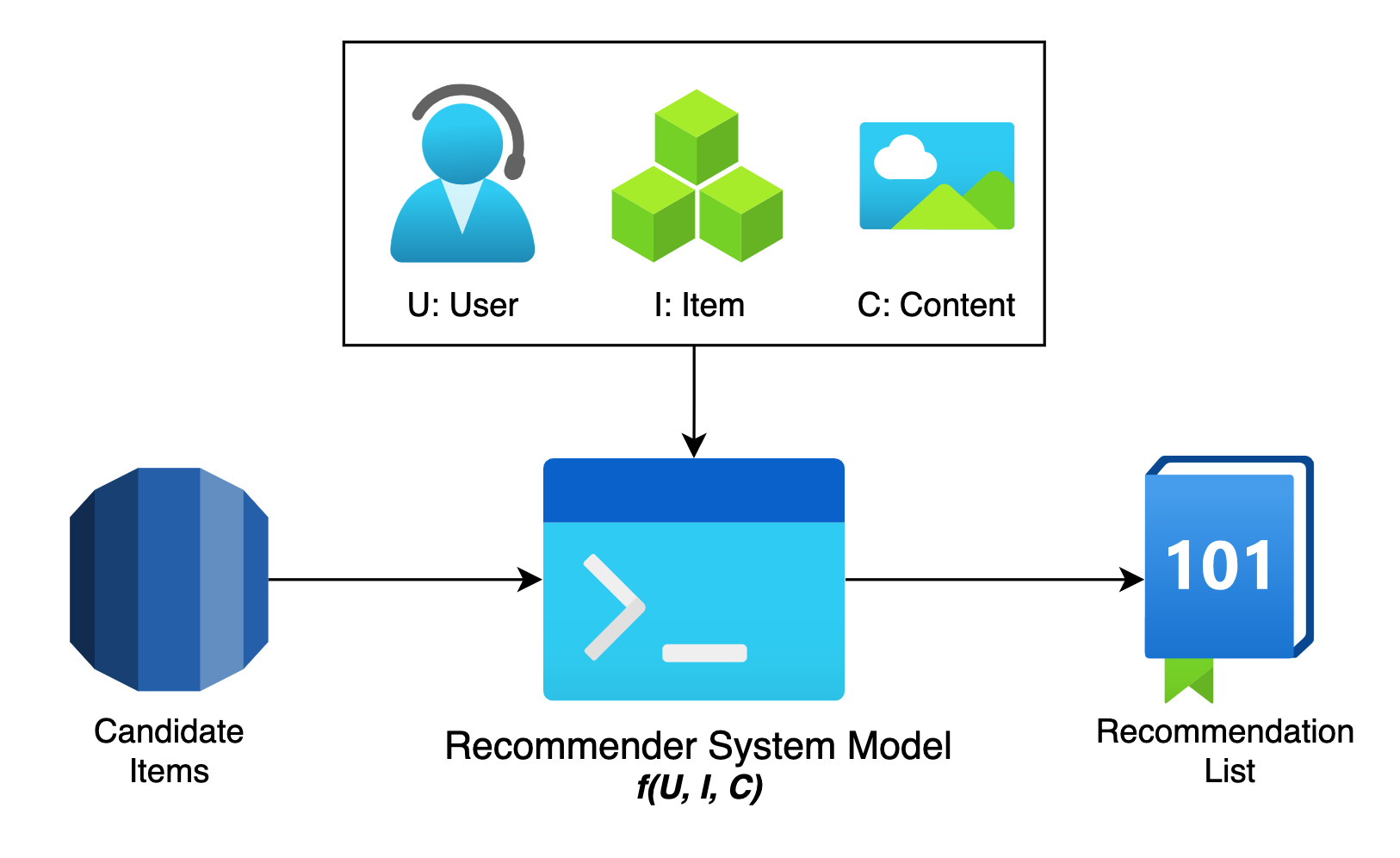

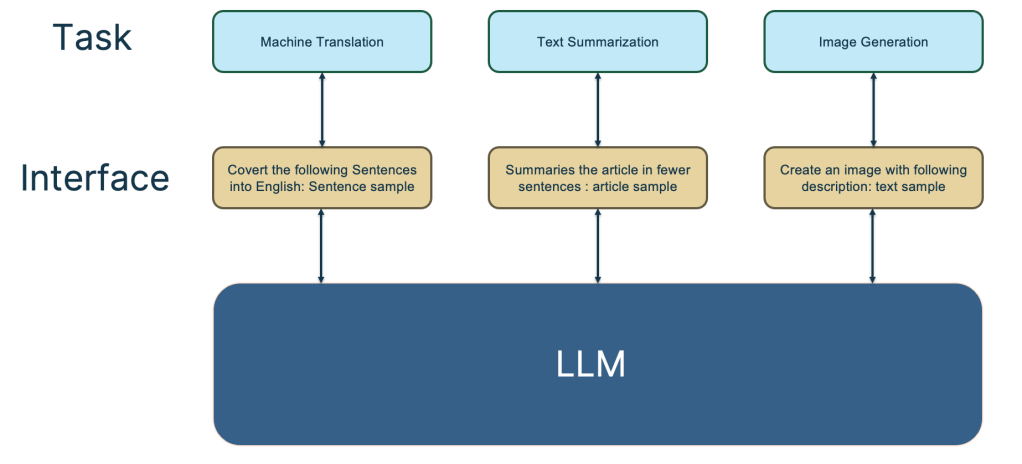

The image above illustrates the characteristics of an ideal Large Language Model (LLM). Firstly, the LLM should possess robust self-learning capabilities. When fed with various types of data such as text and images from the world, it should autonomously acquire the knowledge contained within. This learning process should require no human intervention, and the LLM should be adept at flexibly applying this knowledge to address real-world challenges. Given the vastness of the data, this model will naturally be substantial in size, a true giant model.

Secondly, the LLM should be capable of tackling problems across any subfield of Natural Language Processing (NLP) and extend its capabilities to domains beyond NLP. Ideally, it should proficiently address queries from any discipline.

Moreover, when we utilize the LLM to resolve issues in a particular field, the LLM should understand human commands and use expressions that align with human conventions. In essence, it should adapt to humans, rather than requiring humans to adapt to the LLM model.

A common example of people adapting to LLM is the need to brainstorm and experiment with various prompts in order to find the best prompts for a specific problem. In this context, the figure above provides several examples at the interface level where humans interact with the LLM, illustrating the ideal interface design for users to effectively utilize the LLM model.

Now, let’s revisit the question: Why should we pursue zero-shot/few-shot prompting to complete tasks? There are two key reasons:

- The Enormous Scale of LLM Models: Building and modifying LLM models of this scale requires immense resources and expertise, and very few institutions can undertake this. However, there are numerous small and medium-sized organizations and even individuals who require the services of such models. Even if these models are open-sourced, many lack the means to deploy and fine-tune them. Therefore, an approach that allows task requesters to complete tasks without tweaking the model parameters is essential. In this context, prompt-based methods offer a solution to fulfil tasks without relying on fine-tuning (note that soft prompting deviates from this trend). LLM model creators aim to make LLM a public utility, operating it as a service. To accommodate the evolving needs of users, model producers must strive to enable LLM to perform a wide range of tasks. This objective is a byproduct and a practical reason why large models inevitably move toward achieving General Artificial Intelligence (AGI).

- The Evolution of Prompting Methods: Whether it’s zero-shot prompting, few-shot prompting, or the more advanced Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting that enhances LLM’s reasoning abilities, these methods align with the technology found in the interface layer illustrated earlier. The original aim of zero-shot prompting was to create the ideal interface between humans and LLM, using the task expressions that humans are familiar with. However, it was found that LLM struggled to understand and perform well with this approach. Subsequent research revealed that when a few examples were provided to represent the task description, LLM’s performance improved, leading to the exploration of better few-shot prompting technologies. In essence, our initial hope was for LLM to understand and execute tasks using natural, human-friendly commands. However, given the current technological limitations, these alternative methods have been adopted to express human task requirements.

Understanding this logic, it becomes evident that few-shot prompting, also known as In Context Learning, is a transitional technology. When we can describe a task more naturally and LLM can comprehend it, we will undoubtedly abandon these transitional methods. The reason is clear: using these approaches to articulate task requirements does not align with human habits and usage patterns.

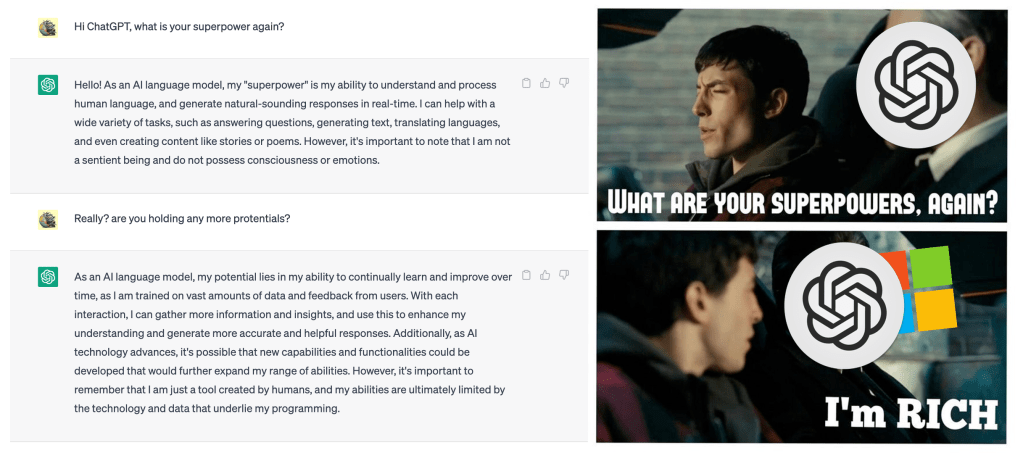

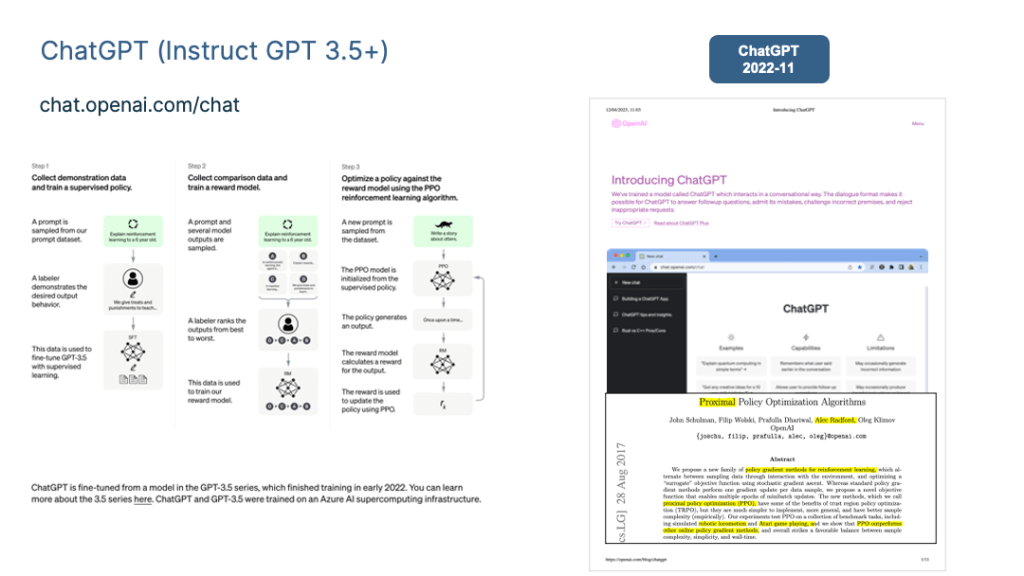

This is also why I classify GPT 3.0+Prompting as a transitional technology. The arrival of ChatGPT has disrupted this existing state of affairs by introducing Instruct instead of Prompting. This change marks a new technological paradigm shift and has subsequently led to several significant consequences.

Impact 1: LLM Adapting Humans NEEDS with Natural Interfaces

In the context of an ideal LLM, let’s focus on ChatGPT to grasp its technical significance. ChatGPT stands out as one of the technologies that align most closely with the ideal LLM, characterized by its remarkable attributes: “Powerful and considerate.”

This “powerful capability” can be primarily attributed to the foundation provided by the underlying LLM, GPT 3.5, on which ChatGPT relies. While ChatGPT includes some manually annotated data, the scale is relatively small, amounting to tens of thousands of examples. In contrast, GPT 3.5 was trained on hundreds of billions of token-level data, making this additional data negligible in terms of its contribution to the vast wealth of world knowledge and common sense already embedded in GPT 3.5. Hence, ChatGPT’s power primarily derives from the GPT 3.5 model, which sets the benchmark for the ideal LLM models.

But does ChatGPT infuse new knowledge into the GPT 3.5 model? Yes, it does, but this knowledge isn’t about facts or world knowledge; it’s about human preferences. “Human preference” encompasses a few key aspects:

- First and foremost, it involves how humans naturally express tasks. For instance, humans typically say, “Translate the following sentence from Chinese to English” to convey the need for “machine translation.” But LLMs aren’t humans, so understanding such commands is a challenge. To bridge this gap, ChatGPT introduces this knowledge into GPT 3.5 through manual data annotation, making it easier for the LLM to comprehend human commands. This is what empowers ChatGPT with “empathy.”

- Secondly, humans have their own standards for what constitutes a good or bad answer. For example, a detailed response is deemed good, while an answer containing discriminatory content is considered bad. The feedback data that people provide to LLM through the Reward Model embodies this quality preference. In essence, ChatGPT imparts human preference knowledge to GPT 3.5, resulting in an LLM that comprehends human language and is more polite.

The most significant contribution of ChatGPT is its achievement of the interface layer of the ideal LLM. It allows the LLM to adapt to how people naturally express commands, rather than requiring people to adapt to the LLM’s capabilities and devise intricate command interfaces. This shift enhances the usability and user experience of LLM.

It was InstructGPT/ChatGPT that initially recognized this challenge and offered a viable solution. This is also their most noteworthy technical contribution. In comparison to prior few-shot prompting methods, it is a human-computer interface technology that aligns better with human communication habits for interacting with LLM.

This achievement is expected to inspire subsequent LLM models and encourage further efforts in creating user-friendly human-computer interfaces, ultimately making LLM more responsive to human needs.

Impact 2: Many NLP subfields no longer have independent research value

In the realm of NLP, this paradigm shift signifies that many independently existing NLP research fields will be incorporated into the LLM technology framework, gradually losing their independent status and fading away. Following the initial paradigm shift, while numerous “intermediate tasks” in NLP are no longer required as independent research areas, most of the “final tasks” remain and have transitioned to a “pre-training + fine-tuning” framework, sparking various improvement initiatives to tackle specific domain challenges.

Current research demonstrates that for many NLP tasks, as the scale of LLM models increases, their performance significantly improves. From this, one can infer that many of the so-called “unique” challenges in a given field likely stem from a lack of domain knowledge. With sufficient domain knowledge, these seemingly field-specific issues can be effectively resolved. Thus, there’s often no need to focus intensely on field-specific problems and devise specialized solutions. The path to achieving AGI might be surprisingly straightforward: provide more data in a given field to the LLM and let it autonomously accumulate knowledge.

In this context, ChatGPT proves that we can now directly pursue the ideal LLM model. Therefore, the future technological trend should involve the pursuit of ever-larger LLM models by expanding the diversity of pre-training data, allowing LLMs to independently acquire domain-specific knowledge through pre-training. As the model scale continues to grow, numerous problems will be addressed, and the research focus will shift to constructing this ideal LLM model rather than solving field-specific problems. Consequently, more NLP subfields will be integrated into the LLM technology system and gradually phase out.

In my view, the criteria for determining whether independent research in a specific field should cease can be one of the following two methods:

- First, assess whether the LLM’s research performance surpasses human performance for a particular task. For fields where LLM outperforms humans, there is no need for independent research. For instance, for many tasks within the GLUE and SuperGLUE test sets, LLMs currently outperform humans, rendering independently existing research fields closely associated with these datasets unnecessary.

- Second, compare task performance between the two modes. The first mode involves fine-tuning with extensive domain-specific data, while the second mode employs few-shot prompting or instruct-based techniques. If the second mode matches or surpasses the performance of the first, it indicates that the field no longer needs to exist independently. By this standard, many research fields currently favour fine-tuning (due to the abundance of training data), seemingly justifying their independent existence. However, as models grow in size, the effectiveness of few-shot prompting continues to rise, and it’s likely that this turning point will be reached in the near future.

If these speculations hold true, it presents the following challenging realities:

- For many NLP researchers, they must decide which path to pursue. Should they persist in addressing field-specific challenges?

- Or should they abandon what may seem like a less promising route and instead focus on constructing a superior LLM?

- If the choice is to invest in LLM development, which institutions possess the ability and resources to undertake this endeavour?

- What’s your response to this question?

Impact 3: More research fields other than NLP will be included in the LLM technology system

From the perspective of AGI, referring to the ideal LLM model described previously, the tasks it can complete should not be limited to the NLP field or one or two subject areas. The ideal LLM should be a domain-independent general artificial intelligence model. , it is now doing well in one or two fields, but it does not mean that it can only do these tasks.

The emergence of ChatGPT proves that it is feasible for us to pursue AGI in this period, and now is the time to put aside the shackles of “field discipline” thinking.

In addition to demonstrating its ability to solve various NLP tasks in a smooth conversational format, ChatGPT also has powerful coding capabilities. Naturally, more and more other research fields will be gradually included in the LLM system and become part of general artificial intelligence.

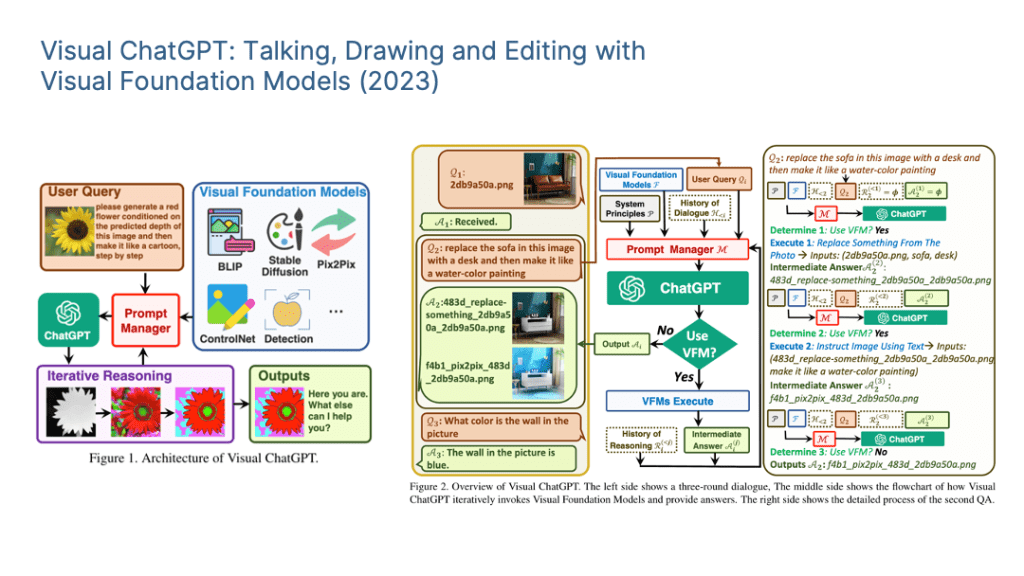

LLM expands its field from NLP to the outside world. A natural choice is image processing and multi-modal related tasks. There are already some efforts to integrate multimodality and make LLM a universal human-computer interface that supports multimodal input and output. Typical examples include DeepMind’s Flamingo and Microsoft’s “Language Models are General-Purpose Interfaces”, as shown above. The conceptual structure of this approach is demonstrated.

My judgment is that whether it is images or multi-modality, the future integration into LLM to become useful functions may be slower than we think.

The main reason is that although the image field has been imitating Bert’s pre-training approach in the past two years, it is trying to introduce self-supervised learning to release the model’s ability to independently learn knowledge from image data. Typical technologies are “contrastive learning” and MAE. These are two different technical routes.

However, judging from the current results, despite great technological progress, it seems that this road has not yet been completed. This is reflected in the application of pre-trained models in the image field to downstream tasks, which brings far fewer benefits than Bert or GPT. The application is significant in NLP downstream tasks.

Therefore, image preprocessing models still need to be explored in depth to unleash the potential of image data, which will delay their unification into large LLM models. Of course, if this road is opened one day, there is a high probability that the current situation in the field of NLP will be repeated, that is, various research subfields of image processing may gradually disappear and be integrated into large-scale LLM to directly complete terminal tasks.

In addition to images and multi-modality, it is obvious that other fields will gradually be included in the ideal LLM. This direction is in the ascendant and is a high-value research topic.

The above are my personal thoughts on paradigm shift. Next, let’s sort out the mainstream technological progress of the LLM model after GPT 3.0.

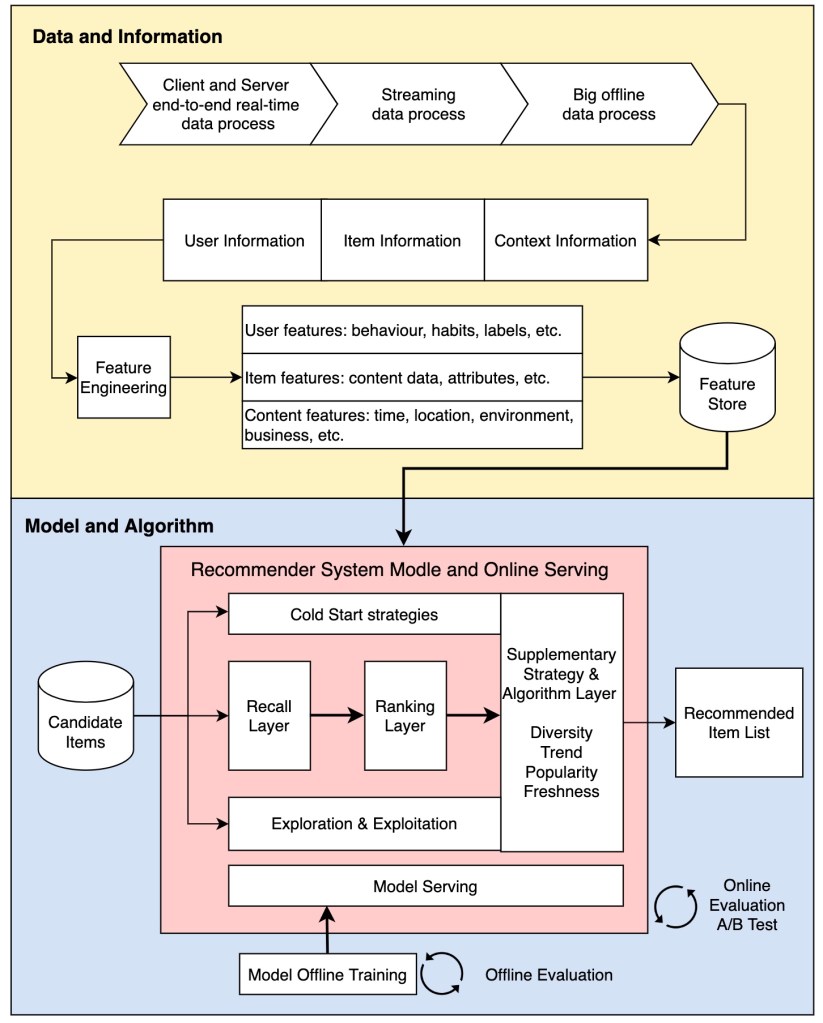

As shown in the ideal LLM model, related technologies can actually be divided into two major categories;

- One category is about how the LLM model absorbs knowledge from data and also includes the impact of model size growth on LLM’s ability to absorb knowledge;

- The second category is about human-computer interfaces about how people use the inherent capabilities of LLM to solve tasks, including In Context Learning and Instruct modes. Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting, an LLM reasoning technology, essentially belongs to In Context Learning. Because they are more important, I will talk about them separately.

Reference

- 1. Vaswani, A. et al. Transformer: Attention Is All You Need. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1706.03762.pdf (2017).

- 2. Openai, A. R., Openai, K. N., Openai, T. S. & Openai, I. S. GPT: Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. (2018).

- 3. Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. (2018).

- 4. Radford, A. et al. GPT2: Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners. (2019).

- 5. Brown, T. B. et al. GPT3: Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. (2020).

- 6. Ouyang, L. et al. GPT 3.5: Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. (2022).

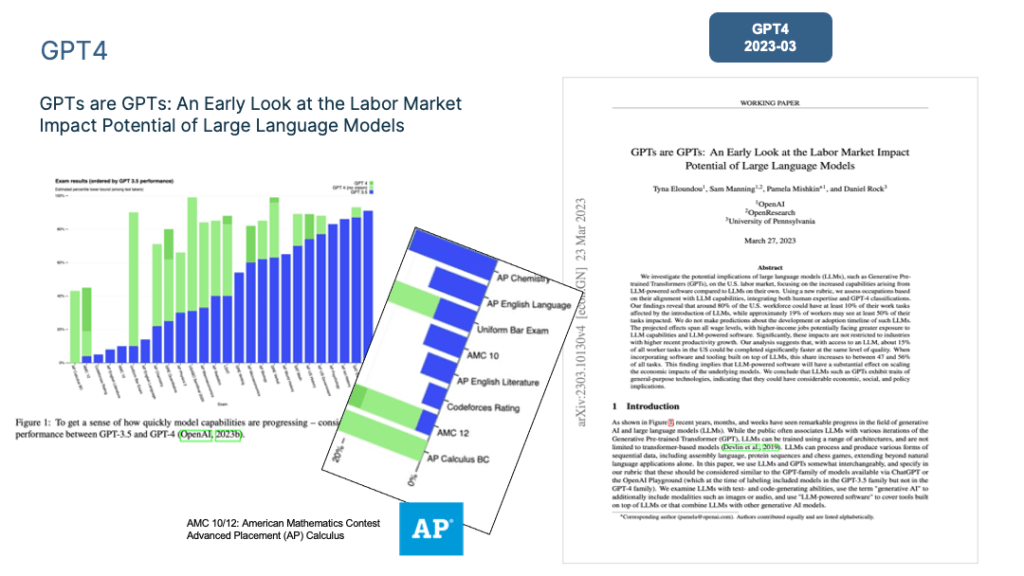

- 7. Eloundou, T., Manning, S., Mishkin, P. & Rock, D. GPT4: GPTs are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models. (2023).

- 8. OpenAI. Introducing ChatGPT. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt (2022).

- 9. Schulman, J., Wolski, F., Dhariwal, P., Radford, A. & Openai, O. K. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. (2017).